The Flowers

Wandering through Dag Hammarskjöld's inner landscapes, from a discovery in his copy of the 'Atlantica'.

Postscript (Autumn 2025)

Long before plans for Frozen Atlantis took shape, the lines by Dag Hammarskjöld quoted above had served as a kind of manifesto on the inner journey leading towards it – a journey the film would eventually come to chart.1

At the time that voyage began, the life and writings of this Swedish diplomat had served as ‘waymarks’ on my own path. The article below stems from a phase in the project of broad curiosity, in which I took first steps exploring alternative modes of storytelling.

There is a line running from that time of free exploration to the first test screenings of what would grow into film. In April 2025, we presented early versions to test audiences at Stockholm and Falun.

Back then, I envisioned the film to open on several ‘balconies’ – vantage points from which the audience would watch the ‘actual story’ unfold. The rough cut we screened began with the lines quoted above – words I had imagined as a frame, if not sum, of the film that followed.

The feedback from the April test screenings was encouraging. Yet as a result, we decided to simplify the film’s opening structure. The quote by Hammarskjöld was one of the darlings that did not survive into the final cut.

And yet, the words have stayed with me – outlining an inner landscape that the film came to explore in visual form.

The story I wrote under the title The Flowers bears witness to moments of resonance I felt with the landscapes that Dag Hammarskjöld explored in his literary work – a side-track I was fortunate to explore as part of the project, and that would ultimately shape its nature.

Before the Harvest

Så vilar himlen mot jorden played the song from the stereo. So rests the sky against the earth.

From the windows of my rental car, I saw the coastal wind caressing the yellow fields.

It was late summer, and the crops had already begun to bow toward the earth. Further along the horizon, light clouds drifted over the dunes that rose like a gentle bulwark against the Baltic Sea.

I was driving down to Österlen, a sunlit corner in the south-east of Sweden. Between the coastal road and the dunes, a few cottages dotted the landscape, hiding among pastures and patches of forest that breathed a resinous fragrance into the balmy morning air of late July.

It was the last stretch of my journey, and the stereo played a recent tribute to the poet whose summer house I was about to reach, almost six decades after his death.

In the rearview mirror of time, the journey had begun two decades earlier.

One of my elementary school teachers was married to a pastor. In his prayer book he carried a set of white preaching bands, and at a moment’s notice, so I imagined, he could transform from layman into priest, ready to perform spontaneous weddings on the spot.

He was a friend of my parents, and our paths crossed again many years later, when I sought his counsel during a family crisis.

“There are two books I read every year,” he mentioned to me on one of these occasions. “Marc Aurel’s Meditations and the Waymarks by Dag Hammarskjöld.”

At the time it was the Roman Emperor rather than the Swedish diplomat who impressed me. Now, on the front seat of my rental car, dog-eared pages of Waymarks fluttered in the winds, the margins full of notes.

The Fragrance of the Soil

My first glimpse of the summer house came from the parking lot: a black roof stretched over the whitewashed walls of a former barn.

Gravel crunched under my shoes as I walked down the narrow lane, the sound of my steps blending with the occasional moo from the fields.

Behind a wooden fence, a few cows grazed, unimpressed by an early-morning passerby. Spots of purple blossoms dotted the pasture dry from summer, in whose middle rose a maypole rose.

A few weeks ago, the country had celebrated the longest day of the year with a night of singing and dancing and the picking of seven flowers said to bring dreams of one’s future love.

Here too, a blue and yellow pennant draped over wilting garlands that bore witness to the the recent holiday. A breeze rustled the brittle wreaths, carrying the earthy scent toward the former farmhouse.

In 1957, Dag Hammarskjöld acquired the estate of Backåkra. It was the year he was appointed to his second term as Secretary-General of the United Nations.

For a while I lingered before the black door, listening to the leaves in the crown of a nearby oak. Steel cables clanged against the two flagpoles bearing the Swedish flag, resembling the sound of wind playing among the masts of moored ships.

The Baltic line here is a black line on the horizon. A short walk from the estate, across the pastures and a coastal forest, the sandy beaches of Sandhammaren line the shore. Here Hammarskjöld’s longing to retreat found an anchor during his time at the UN, a hope to experience nature with all senses: the whispers of the trees, the fragrance of the soil, the caresses of the wind, the embrace of water and light.2

'So That You May Climb to Even Greater Height'

In the 1960s, Hammarskjöld’s retreat was transformed into a museum dedicated to his memory. After substantial renovations, Backåkra had recently re-opened to the public again.

In the weeks before my visit, I had been corresponding with Karin, the museum’s curator. It preserves more than seven hundred objects from the possession of Hammarskjöld.

One of them in particular had brought me to this far-flung corner of Sweden: the ice axe in the first photograph ever taken atop Mount Everest. “So that you may climb to even greater heights”, Sherpa Tenzing Norgay had engraved on a silver hull protecting the shaft of the axe. A year after the ascent, he presented it to Hammarskjöld in Geneva.

Originally, I had come to Backåkra to research the story of the axe further. Yet there was more to be discovered.

Several of the rooms are reconstructions of Hammarskjöld’s Upper East Side apartment, where he lived for eight years during his tenure as UN Secretary-General. The furniture, and even the books, are arranged exactly as in the original apartment.3

As a reader and writer, Hammarskjöld was deeply interested in all sorts of literature, but poetry in particular. Thus, an extensive private library had followed him from Sweden to his diplomatic post in New York.

Today, Backåkra holds over 1500 books, with a similar number kept at the Royal Library in Stockholm. Upon my arrival, Karin showed me the index for the local collection.

Studying this fingerprint of Hammarskjöld’s intellectual world, I began to look forward to the rest of the day, when I would be free to lose myself in his books.

On the way to his study, I followed Karin through the exhibition spaces where I had just seen the glass display case with Norgay’s axe. On a long wooden table, desk lamps illuminated reading copies of books about the Secretary-General’s life. A year after the re-opening, the wood still smelled fresh.

For Swedes of an older generation, the man whom Kennedy called ‘the most important statesman of the twentieth century’ is still the most visible example of their nation’s ideals. Today, memory of Hammarskjöld’s name has faded, while the UN is criticised for being a bureaucratic behemoth no longer capable of living up to its agenda and mission.

From the open loft above the table hung a UN flag. For a moment, I remembered the summit photograph of Tenzing Norgay, showing a small rag of the blue-and-white banner tied to the top of his ice axe, raised into the winds that sweep the top of Everest.

Interviews and archival footage from Hammarskjöld’s two terms flickered across the flat screens on the walls. As I passed, I caught fragments of his voice from the headphones hanging on the wall. His native language still shone through the colour of the vowels and in the melody that carried the English in which he diplomatically defied Khrushchev’s demands to resign from his position.

Exploring the Study

In the next room, two windows flooded the study with the light of Swedish summer. Beside the door stood wooden object with a concave surface.

“The staff had no idea what this thing was – so complicated to vacuum around,” Karin explained. “That was until Kofi Annan visited in 1999,” she smiled. “The Secretary-General was surprised to see an Ashanti headrest from his home country on the floor of a former farmhouse in southern Sweden.”

A glass case against the wall held an antique vase and a replica of the Santa Maria, the ship on which Columbus sailed across the Atlantic. Hammarskjöld had received the model of on the first United Nations Day in office. He originally kept the model on the mantelpiece of his NYC apartment. Beneath it, Tenzing’s axe would later hang.

On the wall behind Hammarskjöld’s desk hung a black-and-white panorama of the Gauri Shankar range in the Himalayas.

“Hammarskjöld took those photographs in 1960,” Karin said. “That year he was on a mission in Nepal. On the last day of his visit, the king lent him his personal plane for a courtesy flight in the Himalayas.”

“He would later publish an article in National Geographic,” she added, pointing to a copy of the magazine on a music stand.4

Reaching behind the frame, Karin unlocked a hinge. The photograph swung open. Behind, seventeen wooden rollers came into view, each tied with white cotton ribbon. With a gentle tug, Karin untied one of them, unrolling a map of the United States.

“A National Geographic Society map cabinet,” she explained. “Every American president since World War II has received one of these.”

“For Hammarskjöld, they made an exception,” she continued with a note of pride.

Beneath the map, I noticed a row of books placed on a low shelf just above the floor, folio-sized volumes that stood against the wall, protected in a plexiglass case.

I squatted down to read the titles. There were some old acquaintances amongst them.

Between books on Greek art or the Impressionists, I spotted Manker’s large-scale volumes on Sámi drums. Further along were seventeenth-century publications on Sweden, including Erik Dahlberg’s Suecia antiqua et hodierna (“Ancient and Modern Sweden”), with its lavish engravings of buildings and monuments of the Kingdom.

Then, among the Latin-titled prints, Olof Rudbeck’s Atlantica – two volumes.

A shiver ran down my spine.

For years, I had been studying this work by one of Europe’s last universal geniuses.

Olof Rudbeck, a professor of anatomy at Uppsala University, published the four volumes of Atlantica from 1679 to 1702. In the monumental work, he presented ‘evidence’ that Sweden was Europe’s first high culture – the cradle of languages and the origin of classical mythology. For him and dozens who followed his ideas, the high civilization described by Plato under the name of Atlantis was, in reality, Sweden (more on this in the About section).

Libraries in Europe preserve several dozen copies of this bizarre yet fascinating work, and whenever I get the opportunity, I study them. However, no catalogue I knew of listed the two volumes in Hammarskjöld’s private library.

What I did know though was that throughout his life, Hammarskjöld collected books on everything Swedish. Besides, he cultivated friendships with bibliophiles such as Uno Willers, head of the Royal Library at Stockholm and a close friend of his.

Still, I was amazed. An earnest reader, Hammarskjöld might well have belonged to the small readership of the Atlantica – or at least to those who could appreciate Rudbeck’s quirky scholarship enough to acquire two historic volumes of the work.

I turned to Karin.

“Is there a way I could see these books,” I asked, pointing to the two volumes behind plexiglass. She thought for a moment.

“Let me talk to Claes,” she replied.

Later that day, Karin’s husband and I returned to the study. Carefully, we lifted the plexiglass case off the books. I picked up the two volumes and placed them on Hammarskjöld’s desk.

“You’ll be all right here, won’t you?” Claes asked.

I nodded.

“And do use the chair,” he said as he headed back to the ticket office. I nodded again, flattered by his trust, standing alone in Hammarskjöld’s study.

Digressions at the Desk

My eyes began to wander over Hammarskjöld’s desk and the chair behind it, over its cognac brown leather backrest, edged with brass rivets. Designed by Carl Malmsten, Karin had told me. On the desktop lay a few personal items: a typewriter under a green protective cover, a lamp, an analogue clock, a miniature UN flag on its pole.

Among them was a further object to which Karin had drawn my attention before, a clay bird used as a paperweight. “The sanningsfågel,” she had explained – ‘the Bird of Truth’. “Sometimes, Hammarskjöld’s friends said, he would turn the bird toward a guest – to make sure that he’d hear the truth.”

I took a seat in the chair. Beneath the desk, I felt my shoes sink into a soft Persian rug. Having arranged the two volumes, I turned the clay bird toward the books, and let my fingers wander over their heavy leather binding.

What will I find?, I wondered. A dedication, perhaps; bookmarks, some personal notes?

As I relished the moment of anticipation, a flicker from the corner of my eye. I turned my head. Behind a stained-glass window with Hammarskjöld’s initials, a cow swung its tail.

A gift from his friend, the painter Bo Beskow, Karin had explained the artwork that blurred the cow into a patch of yellow and blue as it strolled through the pasture.

My view wandered back to the whitewashed surface of the farmhouse wall across the desk. It landed on an abstract painting, again by Beskow.

In 1957, Hammarskjöld invited the painter to visit him in New York. That same year, the Secretary-General had a non-denominational meditation room installed in the UN headquarters.

At first, Hammarskjöld had asked French modernists such as Jacques Villon or Georges Braque to design its wall paintings. As Braque couldn’t travel overseas, Hammarskjöld decided to assign it to Beskow. The draft of his design remained at Backåkra.

Beskow and Hammarskjöld had already met in 1953 – not far from here beyond the dunes, in the cottage Beskow owned at Rytterskulle. That year, he painted Hammarskjöld’s portrait, when he was still working for the Swedish foreign office.

Beskow was among the few people by whom he felt truly seen. The man who first captured Hammarskjöld on canvas became a close friend – perhaps the closest he ever had.

Between the Lines

My gaze returned to the weighty tome in front of me. Carefully, I lifted the cover. With a slight groan, the leather binding bent.

Along the side of the front cover, traces of sealing wax. The paper it once held had been removed. In the upper right corner was Hammarskjöld’s ex libris, the paper emblem he used to mark his books. A pair of crossed hammers with his monogram, the UN logo below.

“Call me hammer-shield”, the diplomat would tell journalists struggling with his name. “That’s actually what it means.”

I touched the corner of the first page. The seventeenth-century paper, made from cloth rags instead of woodchips, felt thick and heavy. I began turning the pages.

The margins did contain some notes, I discovered browsing through the volumes; some jottings in ink and pencil. From documents I had seen in the Royal Library in Stockholm, I was familiar with the Secretary-General’s minute handwriting, which colleagues at the UN referred to as ‘Hammarskjöld’s Arabic’.

These annotations, however, stemmed from previous owners. Disenchantment set in as I turned the pages. There seemed to be no traces of Hammarskjöld himself.

I flipped through the Atlantica, through its familiar maps and illustrations, disappointed.

Until – until I turned that page.

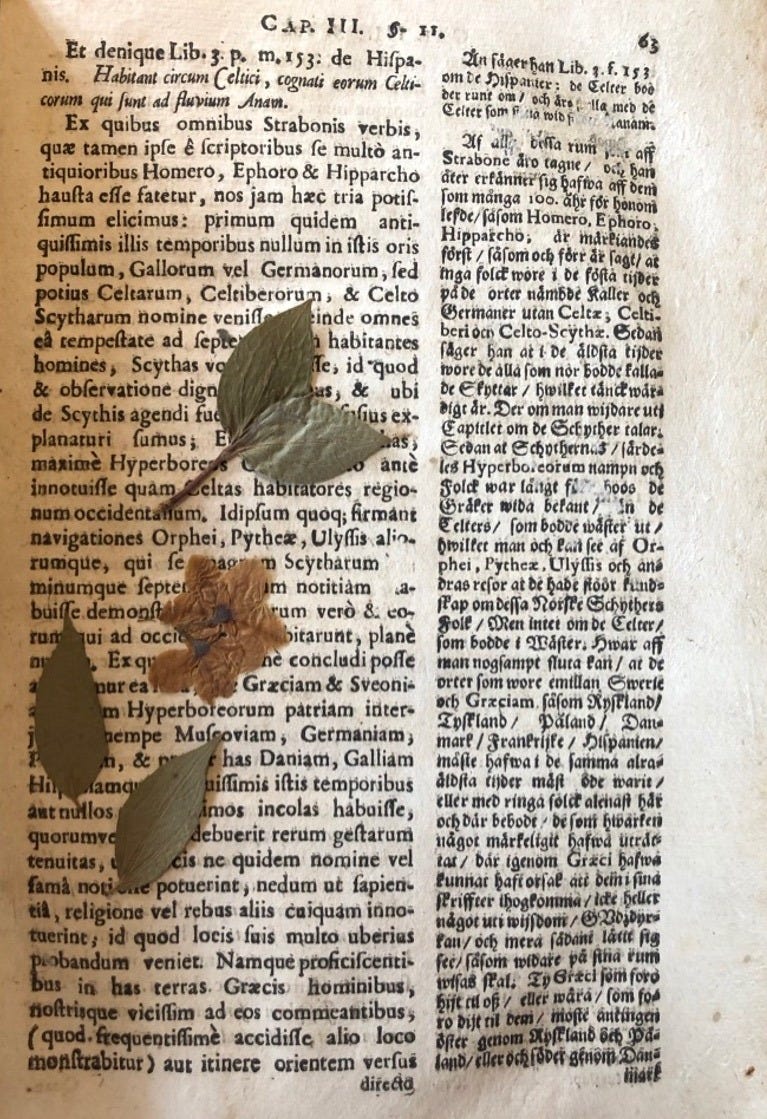

Chapter Three, “On the Time when Sweden was First Settled and by What People”. On the column of Latin words, just beneath the heading, lay two pressed blossoms, four leaves, and a stem.

My heart missed a beat.

What if? the thought shot through my head: what if Hammarskjöld had picked these plants?

I couldn’t know if or when or where he had done so. I didn’t even know what I was looking at. But as to why he would have done that – after all that I had read before about the man, his poetry, his love of nature, and his hope to retreat here, to a home secluded in the nature of southern Sweden – the answer felt intuitively clear.

'All Sorts of Plants Salute the Lord of this House'

From the desk, my gaze wandered out the window again, across the pastures leading to the sea. Somewhere down there stood the first house Hammarskjöld had bought in Österlen. Backåkra, where I had come, had been the second.

In 1953, Hammarskjöld met Beskow at his place to have his portray painted. He knew the landscape from cycling tours he undertook as young man, along the gentle dunes and the wild shores covered in driftwood and shipwrecks.

In the course of their sessions, Hammarskjöld had told Beskow how much these surroundings resonated with him. It had registered with the painter that his new friend was seriously looking for a place to retreat, somewhere in the green and close to the sound of the Baltic waves.

Just after Dag had started his position in NYC in 1953, Beskow wrote to him about a farmer selling a house nearby. Hammarskjöld took the opportunity and bought the old fisherman’s cottage near Hagestad.

His duties in New York allowed the diplomat to drop by only a few days each year. While Hammarskjöld was across the Atlantic, Beskow oversaw the renovations of the house his friend had bought.

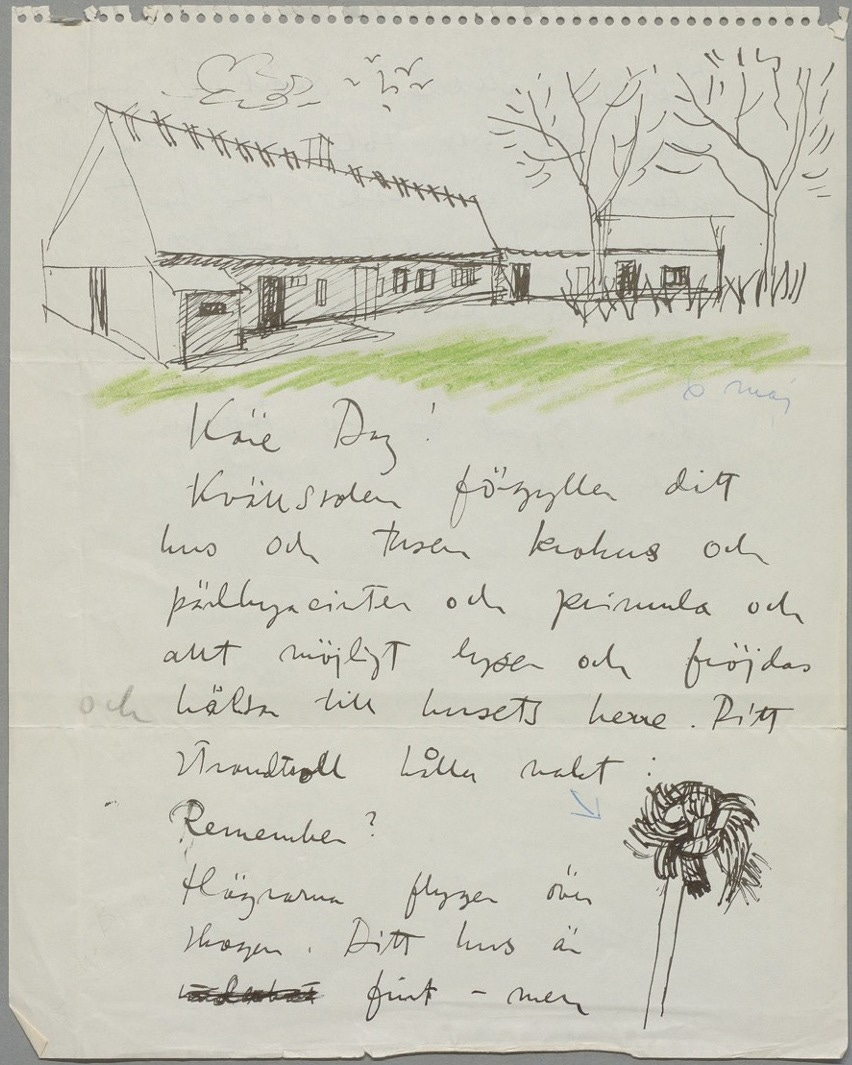

With his letters, he sent regular reports and photographs. A few weeks earlier, I had read some of them in the Royal Library in Stockholm. Beskow, so I had learned on that visit to the Special Reading Room, had the wonderful habit of illustrating letters he sent to close friends.

In one of them from 1954, Beskow drew the cottage his friend had acquired the year before. A carpet of green pours out in front of the house. In the clear sky above, a flock of birds passes over (perhaps on their way back from the south?). Below, bare birch trees and hedges that still await the touch of spring.

“The evening sun gilds your house,” Beskow wrote, “and thousands of crocuses and grape hyacinths and primula and all sorts of plants gleam and delight, and salute the lord of this house. Your beach troll is keeping guard.”

Then, in English: “Remember?”5

Remember.

The year before, Hammarskjöld had spent a few summer days in Österlen. He passed them with Beskow watching birds, chasing butterflies, picking flowers, collecting shells and draping sea weed on driftwood, leaving behind bearded faces on the beach. The coming year, however, he could not be there, to witness as spring arrived at his new place.

In a a tender gesture, Bo drew for his friend what he was denied to see.

Waymarks

In 1953, Hammarskjöld had become the leader of the UN when the young institution was in a deep crisis. He had a reputation as a hard-working diplomat, a self-disciplined Protestant, a somewhat aloof intellectual who kept his distance.

During his tenure as Secretary-General, the UN emerged as a protector of new democracies, inconvenient to both the Eastern Bloc and the West alike. Hammarskjöld’s esteem rose as he defused international conflicts. At the height of the Suez Crisis, the coasts of Österlen rose on his horizon of longing – a harbour of inner peace that, ultimately, remained out of reach.

The world is slightly mad, and the more you are compelled to witness this, the more you long for good, wise friends in a quiet nook, where you don't listen to the radio and are more interested in the migrating birds (that probably by now, passing Rytterskulle, have returned to the frogs in the Nile (not minding Nasser).

Dag Hammarskjöld, Letter to Bo Beskow, 15 September 19566

Behind the façade of the skilled and effective diplomat, Hammarskjöld longed deeply for friendship, for quiet, for nature. The life he chose – or that chose him, as he put it – left many of those longings unfulfilled.

Throughout his adult life, Hammarskjöld gave voice to his doubts, inner conflicts, and insights in writing. A manuscript collecting his reflections and poems was found when friends cleared out his New York apartment after his death. Poeticised by W.H. Auden, it eventually appeared in English as Markings (from the original Vägmärken, literally Waymarks).

The Consolation of Flowers

What is my role – what is our role – in creation? This question runs through the manuscript of Waymarks. For him, much of the answer rooted in a deep sense of spirituality, revolving around perceiving human existence as part of something larger. Experiencing nature with all his senses offered glimpses of insights that he sought to capture in his writing:

The language of flowers, mountains, shores, human bodies: the interplay of light and shade in a look, the aching beauty of a neckline, the grail of the white crocus on the alpine meadow in the morning sunshine –– words in a transcendental language of the senses.

Dag Hammarskjöld, Waymarks, 1950 (p. 42)

Yet there were aspects of the human experience to which Hammarskjöld remained only a bystander. He was never married, and we know of no significant relationships he maintained. Beskow was one of the friends Hammarskjöld trusted enough to share the dilemma he felt between achieving personal happiness and following a higher calling:

When I see other possibilities (like yours), I can feel a short pain of having missed something, but the final reaction is: what must be, is right.

Dag Hammarskjöld, Letter to Bo Beskow, 12 November 1955 7

After Beskow bought his home at Rytterskulle in 1945, the cottage on the hill with its large garden had become a place of inner nourishment for the artist. For long periods during the year, he and his wife Greta retreated there from Stockholm.

Through his friend in Österlen, Hammarskjöld communed with a world that for him felt mostly out of reach. When he visited in the summers, he and Beskow would try the herb liquors he concocted from the plants in his garden, drink red wine, and talk into the wee hours about art, international affairs, or matters of the heart.

For both men, the garden was a place to reconnect with what mattered to them, to feel themselves as part of nature’s cycles of growth, maturity, and decay:

When the nightmares set in, I go out with a glass of sherry in the herb garden and watch as the sun rises over the hills and feel how the herbs play their organ of scents to excess. It is remarkable what a garden helps. Banal – but it's banal truths for which one sometimes must be grateful.

Bo Beskow, Letter to Dag Hammarskjöld, 23 August 1953 8

With his letters, Beskow shared deeply from the world for which his friend longed. Each brief visit to Österlen refreshed his memory that across the Atlantic, there was a place abounding in all that nourished his inner life – close friends, nature, silence, and literature.

I dream of private writing down at Hagestad after the five years of fighting here. Then, if ever ...

Dag Hammarskjöld, Letter to Bo Beskow, Summer 1953 9

Seventeen Syllables

From his leather chair, I watched the afternoon light from the window cast shadows on the pages of Rudbeck’s Atlantica.

Carefully, I picked up the withered leaves, turning their brittle stems between my fingertips. Over time, the blossoms had turned a withered yellow, their faded colour speaking of an attempt to preserve what could not be preserved.

Buddha had tried this too, the thought shot through my mind.10

When Siddhartha married, he received a palace that was surrounded by the Garden of Four Seasons. He loved the early blossoms that reminded him of the beauty of his wife. And so Siddhartha gave her the room overlooking the Garden of Spring.

However, Siddhartha soon had to witness its flowers wither away in the tropical climate. His joy changed to grief. The rapid decay of the sensual pleasures that plants exuded, so legend has it, led him to gather and carefully preserve flowers. Thus the tradition of pressing flowers began, in an effort to keep their beauty from decaying.

Hammarskjöld was familiar with the language of flowers and seasons as expressed in Eastern traditions such as ikebana or the haiku. When his friends cleared out his NYC apartment after his death, they found a copy of Harold G. Henderson’s Introduction to Haiku among the books on the bedside table.

In 1959, Hammarskjöld had written a series of these seventeen-syllable poems. The poems recall his childhood in Uppsala – memories of collecting plants and insects around the castle where he grew up, capturing impressions of Swedish nature as it moved through the seasons.

In the shadow of the castle

The flowers closed

Long before nightfall.Dag Hammarskjöld, Waymarks, 1959 (p. 178).

It seemed as if this genre of Japanese poetry, tied so closely to plants and the seasons, had resonated with Hammarskjöld in the last years of his life. At this time, he sought to reconnect with early memories of the home and the nature he had left behind. “Seventeen syllables,” he began the 1959 haiku cycle, “Opened the door / To memory, to meaning.”11

I arched my back and considered further.

If Hammarskjöld himself pressed these plants in his Atlantica, then this copy must have been near the place where he picked them. Reflecting on this assumption, my view wandered through the stained-glass window again, toward the horizon.

From somewhere in the pasture, I heard mooing.

The Search Begins

After taking some photographs of the plants, I rose from the desk and went in search of Karin.

“I’m sure Dag left them in there”, she grinned ear to ear after I had shared the find.

Together, we checked the local index of Hammarskjöld’s books. Olof Rudbeck, Atland eller Manheim, vol. 1 and vol. 2, it read.

“Are there more detailed records of how and when Hammarskjöld would have acquired his copies of the Atlantica?” I asked.

Karin shook her head.

I need an expert on historical plant specimens, I texted my librarian friend Peter in Uppsala as I walked back the gravel road to the parking lot, I adding a few snapshots to the message.

I zoomed in on the photographs once again. The penciled note from the inside of one of the bindings caught my eye. In Swedish handwriting, a ‘head librarian’ had noted that the book was cleared to be sold off by the ‘University Library’.

I fired away a second message. And who could help me track down former head librarians in Sweden?

Then, I looked up from the screen. In the pastures, a few cows sank their heads into the sun-dried grass. A little further on, I spotted a meditation circle on the site that Hammarskjöld had originally reserved for a small chapel.

Could it have been some flower he picked around here?, I wondered.

My view roamed across the fields. Behind the wooden fences, ghost-like patches hovered over the grass, poplar fluff stirred by the breeze from the sea.

I don’t even know what to look for, I realised, and got into the car.

Lessons in Botany

When I opened my laptop back in Stockholm, the first replies to my queries had come in.

From a colleague in Gothenburg I learned that the pencilled note in the Atlantica had been written by a head librarian at the Helsinki National Library (still called University Library back then), in charge from 1934 until 1954. Hammarskjöld’s copies – or at least one of them, so it now seemed – had probably been sorted out for sale before he left for the UN.

The books may have been among the weighty folios he packed for New York, I thought; trusted companions travelling with him from Sweden. In my mind’s eye, I could see a phalanx of staff on a rural airstrip near Stockholm, manhandling book crates bound for the Upper East Side.

Picking flowers and chasing insects counted among the child-like joys in which Hammarskjöld and Beskow indulged during the precious summer days they shared in Österlen, and from which he returned rejuvenated to New York.

Exhibited in the same glass case that kept the ice axe, I remembered his atlas of butterflies, and the handwriting of an eleven-year-old pupil across the open title page: Dag Hammarskjöld 1916, Castle, Uppsala.

Collecting and identifying specimens of plants and insects was a hobby dear to many Swedish children at the time. In Sweden, creating herbaria from pressed plants had a long tradition in schools. After summer vacation, children returned from all parts of the country with their harvests that were then presented and identified at school.

Hammarskjöld grew up in this tradition. His home town Uppsala had been the place where Carl Linnaeus devised his System of Nature. For this eighteenth-century botanist, plants and the divine order he discerned in them were similar to what Hammarskjöld, in his own poetry, called “words in a transcendental language.”

Linnaeus dedicated his life to deciphering this hidden language of the divine. For Hammarskjöld, too, knowing nature was part of a spiritual path, and in this Linnaeus had been a guide. In his NYC apartment, historical editions, commemorative coins, and paintings of the “Flower King” filled a shrine-like niche.

The coins on top of his shelf date from 1957, the year Sweden celebrated the 250th anniversary of Linnaeus’s birth. The same year, Hammarskjöld gave the presidential address at the annual meeting of the Swedish Academy. As a member of the committee that awards the Nobel Prize, be presented a paper “The Linnaeus Tradition and Our Time.”

Legend has it that Hammarskjöld prepared the manuscript just days earlier, while sitting in the UN assembly as an Indian delegate monopolised the floor with a tedious monologue. The speech voiced a deep admiration for the wonder that Linnaeus rekindled in nature: his ability to read the small print in a language that for Hammarskjöld, too, expressed the harmony in God’s creation:

As an observer and a name-giver, Linnaeus taught us to see with insight, but freely as when ‘it is ten in the morning in the head and heart.’ With the creative power of the poet, he showed us how better to capture and hold the elusive experience of the moment in the net of language.

Dag Hammarskjöld, The Linnaeus Tradition and Our Time (1957) 12

In several of his 1959 haiku, Hammarskjöld recalls the greenery around Uppsala Castle where he had gone on his first herbationes as a young boy – the hands-on explorations of the natural world that Linnaeus had introduced into the university curriculum.13

However, since Hammarskjöld started his job at the UN, it had become increasingly difficult for him to immerse in nature this way, even for a few days. In 1959, he was midway into his second term. Crises such as the one escalating in Laos only allowed for two brief visits to Backåkra.

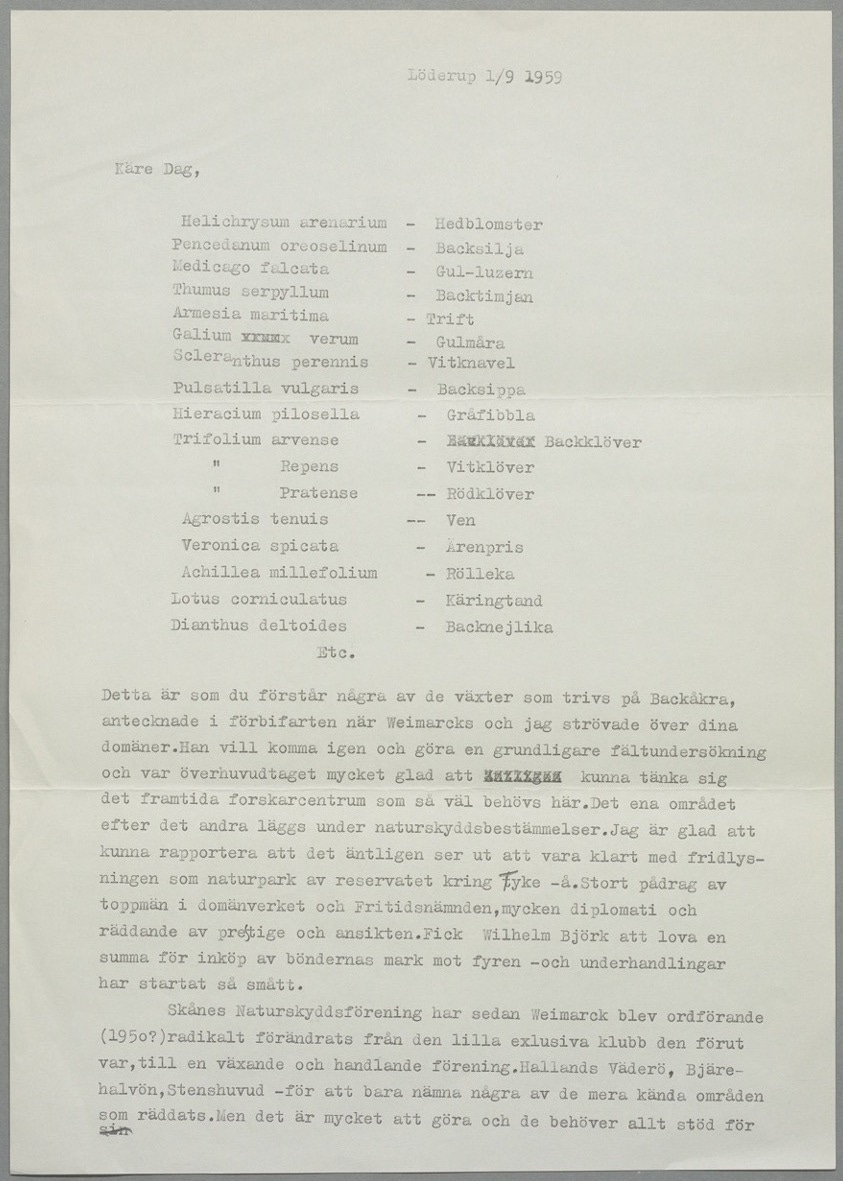

In the meantime, Beskow carried forward the plans they had made for the estate and wrote to his friend about the progress. One of the letters Beskow sent late that summer opens with a list of Linnaean plant names, along with their Swedish counterparts.

This is to inform you about some of the plants that grow on your estate, he explained after an inspecting stroll he had taken across the property Hammarskjöld acquired in 1957. Both shared the hope to turn it into a protected area – a place that would allow future generations to learn to read in that ‘language of flowers’.

Botanical Revelations

A few days after my return from Backåkra, the mails that I had sent off in search for answers had spread out. Among the echos I received was a reply from Mats, an expert on historic plant material at Uppsala University. On the way to Stockholm, I had forwarded my shots from Hammarskjöld’s Atlantica to him.

“Seems like Philadelphus coronarius,” his email read, which I now opened back in the Royal Library.

Immediately, I looked up the Linnaean Latin.

“Mock-orange.” “White pipe tree.”

The sweet fragrance of spring walks in Rome returned to me, and I remembered the cascades of white blossoms spilling over ruined walls.

“In general, it’s difficult to date historic plant specimens,” his mail continued. “Could be a few decades, but also a few centuries.”14

The specimens could have been placed in the book much earlier, long before it was sold in Helsinki. Someone probably checked the volumes beforehand – and yet, even then, it is possible that the flowers simply went noticed.

So perhaps he had picked them, I thought. There seemed to be no way to prove it. But all ambiguity aside, which the academic in me acknowledged, I wanted the dots to connect.

A Picture Forms

I began to imagine how he had picked the flowers, on a brief escape from his apartment on the Upper East Side, during a stroll through Central Park.

A picture began to form in my mind: Hammarskjöld at his desk in the last summer of his life. That evening, Sweden must have felt far away. The year before, in 1960, a humanitarian crisis had begun to escalate in Africa.

He had already travelled to the Congo three times. For Hammarskjöld, retreating to his homeland had not been an option. In New York, debates on how to resolve the Congo Crisis trailed his trips around the globe.

Perhaps it was after one of those days in the UN assembly – on the way home, with dinner guests expected – that he asked his driver to stop near Central Park.

Behind the gates, the mock-orange blossoms perfumed the evening air.

Perhaps they kindled one of the “elusive experiences of the moment” as he inhaled their fragrance amid all the human folly and destruction he was grappling with. The flowers were in bloom again, as they had been the Junes before – their blossoms reminding of the restorative power that, even in the light of disenchantment, abides in nature’s cycles.

But it was an uphill battle. The summer before, Congo had elected a government. A few months later, Belgian forces began their withdrawal. Six decades of colonial rule had come to an end. Congo had become independent.

Yet with Western and Soviet intelligence agencies operating in the background, factions and mining companies quickly began vying for control of the country’s rich resources. In 1960, the new republic under President Lumumba became a member of the UN.

A year later, Congo’s elected head of government was assassinated. The troops that the UN had dispatched to stabilise the young democracy had failed.

Instead, the Blue Helmets soon found themselves fighting rebel troops and mercenaries, backed by Belgian mining companies and foreign intelligence services.

It was a mess, to say the least.

The morning after that imagined visit to Central Park, Hammarskjöld’s driver was already waiting to take him back to the UN. The night had been short, and his exhaustion deepened by the day. As he gathered his thoughts for the day in his study, his glance passed over Beskow’s latest letter, and the still-fresh blossoms he had picked the night before.

A sweet fragrance lingered in his study.

He stretched his arms from his desk chair. The muscles around his neck felt tense. Then, his ears caught the ticking of his watch beneath the sleeve.

For one last moment, he leaned back in his chair. Gently, he twisted the stems of the plants between his fingers, watching the yellow pistils shift at the edge of his vision as he drifted into thought. Toward the windows, a humming A/C blocked his view.

“This will be the closest I get this year,” he may have thought as he took a last inhale of the fragrance that still lingered in the blossoms.

Perhaps it was then that he reached behind him, toward the large volumes he kept on the floor. From their row, he grabbed one of the heavy Atlantica folios.

And as he placed the white blossoms between the pages of Rudbeck’s learned madness, he thought of his hometown, where the volumes had come off the press, the nearby castle where he had grown up, the trees and flowers growing on its slopes, and the treasured days of childhood foraging – memories that rose for a brief moment before he closed the leather cover.

Stale air escaped from the pages, tinged with a faint note of citrus.

Eternal Recurrence

It was weeks later that Hammarskjöld got a few days of rest – not in Sweden, but along the Hudson River. At Brewster, the diplomat kept a cottage where he retreated with a few close friends.

They had never seen Hammarskjöld so exhausted and gloomy as in that August, some of them later remembered. Most days, they recalled, he spent alone outside – writing or listening to the birds in the hour before sunrise.

A few poems exist which Hammarskjöld composed during this time. One of them describes a meadow near Poughkeepsie.

Seven weeks earlier, he recalled, around the weeks of midsummer, the same meadow had been white with ox-eye daisies. It was a sight that reminded him of the precious weeks so dear to his home in Sweden – of wandering barefoot across the grass, of picking the seven flowers that, placed under the pillow, carry dreams revealing the future partner. And yet, here too, across the fields of America, nature had offered glimpses of that annual wonder of renewal:

Seven weeks have gone by

Seven kinds of blossoms

Have been picked or mowed.

Now the leaves of the Indian corn grow broad

And its cobs make much of themselves,

Waxing fat and fertile.

Was it here,

Here, that paradise was revealed

For one brief moment

On a night in midsummer?Dag Hammarskjöld, Waymarks, 1961:18

For a while, I watched the wind rustle the leaves over Humlegården Park, still caught in the image that had spun in my head. From a distance I heard bell ring as the watchman announced the end of reading time.

I was about to close my laptop and call it a day when another mail popped up in my inbox. It had been the middle of the night in NYC when I had written to Daniel at the Botanical Garden in Manhattan earlier that day.

“What about Philadelphus coronarius in Central Park in the years around 1960”, I had asked.

“Frederick Olmsted, one of the designers of Central Park, was fond of Philadelphus, Deutzia, Forsythia, Rhodotypus, Syringa and other profusely-flowering shrubs that would make a dramatic show, fill large spaces and withstand the volume of traffic in Central Park”, he now replied. “These shrubs were planted early in the Park’s history and many of them have persisted to this day.”

“Today, Philadelphus coronarius blooms between late May and early June in Central Park”, Daniel continued. “In recent decades, the flowers have begun blooming earlier each year as global temperatures increase.”

“The phenomenon is called phenology,” he concluded his mail. “I’m sure DH would have been interested in it.”

Gethsemane 1961

Dag Hammarskjöld died on 18 September 1961, when his plane crashed over Central Africa. He was on the way to negotiate a cease-fire between the UN troops and Katangese rebels.15

The Secretary-General’s bed from the night before was untouched, his companions later reported. After the staff and guests had left to get a few hours rest, Hammarskjöld had gone out in the garden.

Dag spent his last night outdoors, a close friend recalled.16

Beneath rustling leaves and among the scent of flowers, he had waited for the birds to begin their morning song. ◆

Further Readings and References

All translations and photographs are my own unless stated otherwise.

A previous version of this article was first published on Too Long, Didn’t Read, an online platform we launched to explore alternative forms of storytelling. It is reposted here together with a postscript and minor modifications to content, layout, notes, and updates of links.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Daniel Atha, Claes and Karin Erlandsson, Mika Hakkarainen, Stephen Harris, Mats Hjertson, Anders Larsson, Peter Sjökvist, and Anna Svensson for their support and feedback.

Today, the estate Hammarskjöld acquired at Backåkra in 1957 serves as a museum and residence for the Swedish Academy. It is open to visitors during the summer months.

Bo Beskow recounts his friendship with Dag Hammarskjöld in his book Dag Hammarskjöld. Strictly Personal, Garden City 1969.

I quote Hammarskjöld's Vägmärken in Leif Sjöberg’s translation that was 'poeticised' by W.H. Auden (see below, note 1). The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation has also published an edition and translation by Bernhard Erling online.

So far, the provenance for Hammarskjöld’s Atlantica can be traced only as far as Helsinki National Library. I was informed that there are no records indicating when or where the copies now at Backåkra were sold.

In 2018, Hammarskjöld’s papers were declared part of the UNESCO Documentary Heritage. They can be consulted at the Royal Library in Stockholm (=National Library of Sweden).

After this article was first published (see the introductory note above), curator Karin Erlandsson and her daughter Kristina published a number of histories of objects from Hammarskjöld’s collection as part of their book Dag Hammarskjölds Backåkra. Platsens magi och föremålens historia, Malmö 2021:

Tenzing Norgay’s ice axe: pp. 120–2

Beskow’s painting for the meditation room: pp. 133–6

the National Geographic map cabinet: pp. 142f.

the Bird of Truth: pp. 144–6

Ashanti headrest: pp. 168–70

p. 89 on ‘Hammarskjöld’s Flowers’, of which I am proud the authors integrated them into their presentation.

The fisherman's cottage Hammarskjöld already bought in 1953 still exists. It has remained in the family's possession. It lies in a secluded spot, and its location is kept within the family.

Please note the general bibliography available here.

Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings, tr. Leif Sjöberg and W.H. Auden, New York 1966 (first published London 1964), p. 56.

See Dag Hammarskjöld, Markings, 1951 (p. 77).

Anne Whidden has recently published a superb piece on Hammarskjöld’s NYC apartment and the rugs that artists like Edna Martin produced for him, see her article on The Swedish Rug Blog.

Dag Hammarskjöld, “A New Look at Everest”, National Geographic Magazine, January 1961.

National Library of Sweden, MS L 179:1:10 (letter from 6 May 1954): “Kvällssolen förgyller ditt hus och tusen krokus och pärlhyacinter och primula och allt möjligt lyser och fröjdas och hälser till husets herre. Ditt strandtroll håller vakt. Remember?”

Quoted from Beskow, Dag Hammarskjöld, p. 60.

Quoted from Beskow, Dag Hammarskjöld, p. 37.

Stockholm, National Library of Sweden, MS L 179:1:10: “När mardrömmerna sätter åt går jag ut med ett glas sherry i kryddträdgården och ser solen gå upp over kullarna och känner örternas doftorgel spela för fullt. Det är märkvärdigt vad en trädgård hjälper. Banalt, men banala sanningar får man vara tacksam för ibland.”

Quoted in Beskow, Dag Hammarskjöld, p. 17.

Hammarskjöld, Markings, 8.4.59 (p. 175).

The speech is published in Servant of Peace: A Selection of the Speeches and Statements of Dag Hammarskjöld, ed. Wilder Foote (New York: Harper & Row, 1962) 151–59.

The eight historical trails (herbationes) that Linnaeus started at Uppsala still exist and are described on this page of Uppsala City.

A few months after my visit to Backåkra, I viewed some historic specimens of Philadelphus coronarius in the collections at Oxford. The flowers stemmed from the herbarium of Robert Bobart, a seventeenth-century botanist. Bobart’s historic specimens at Oxford seemed strikingly similar to the ones I discovered in Hammarskjöld’s Atlantica.

Until today, the reason for the crash near Ndola in today’s Zambia remains disputed. In 2018, the UN re-opened the case. The case has inspired authors as well as directors; see e.g. the investigation by the journalist Susan Williams, Who Killed Hammarskjold? The UN, the Cold War and White Supremacy in Africa (2nd and rev. ed., London, 2016). In 2019, the Danish journalist Mads Brügger published his movie documentary Cold Case Hammarskjöld on the diplomat’s death. In 2023, the film Hammarskjöld. Fight for Peace by Per Fly followed.

The friend who related this episode was the diplomat and philologist Sture Linnér. Hammarskjöld spent his last nights in Linnér’s villa at Leopoldville. See Beskow, Dag Hammarskjöld, p. 186.