Atlantis Ablaze

On the Great Fire of Uppsala (1702) that turned the collections and printing projects of Olof Rudbeck to ashes.

This article was first published as an introductory text on our object database Reaching for Atlantis. It is reposted here with minor modifications and updates.

Save the Books!

Twin torches, the cathedral spires reached into an orange sky. On a nearby roof, their glow lit up the contours of an elderly face. Mouth agape, the man raised his view to the flames creeping up the church, his gaze locked on a printed sheet that danced between its towers, light and effortless as a swallow in flight.

Below, the heart of Swedish learning was ablaze.

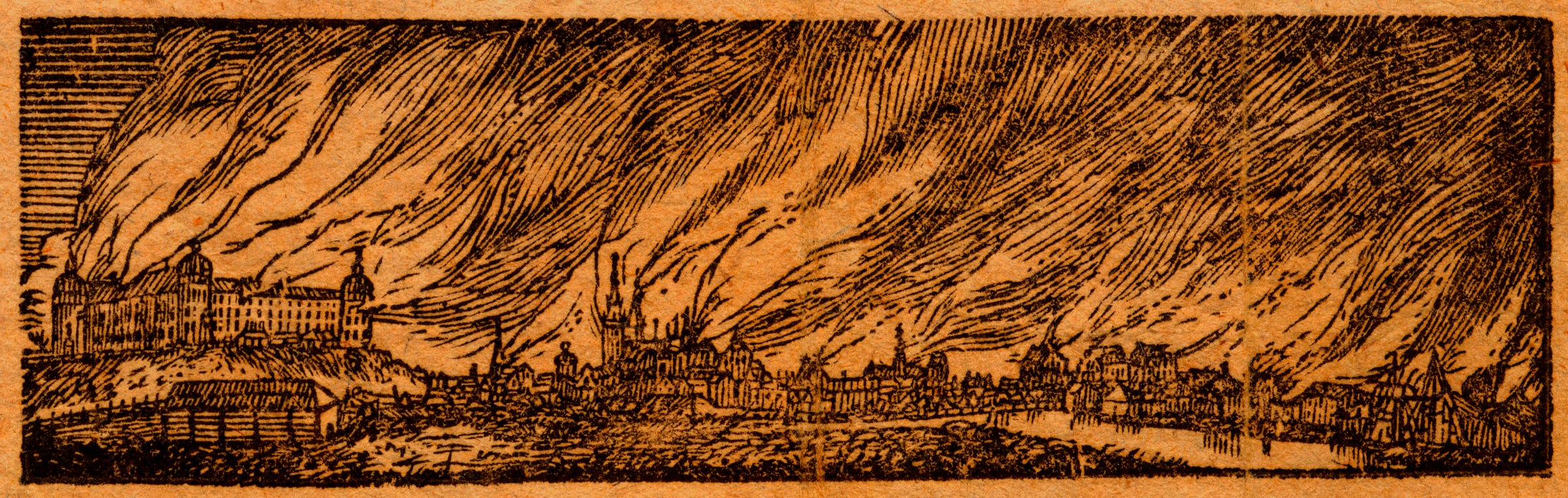

The Great Fire of Uppsala had started after dusk on 15 May 1702, on the other side of Fyrisån River.1 Between crackling roofs that sent sparks into the night sky, families fled beneath a dome of eerily lit smoke; clamouring residents who tried to escape with the few belongings they could carry.

Against their streams, firemen fought their way, water sloshing in their buckets. As they moved between the walls of fire, the men buried their faces in their elbows, eyes squinted against the acrid fumes.

Through the thick smoke, a voice boomed across the cathedral square.

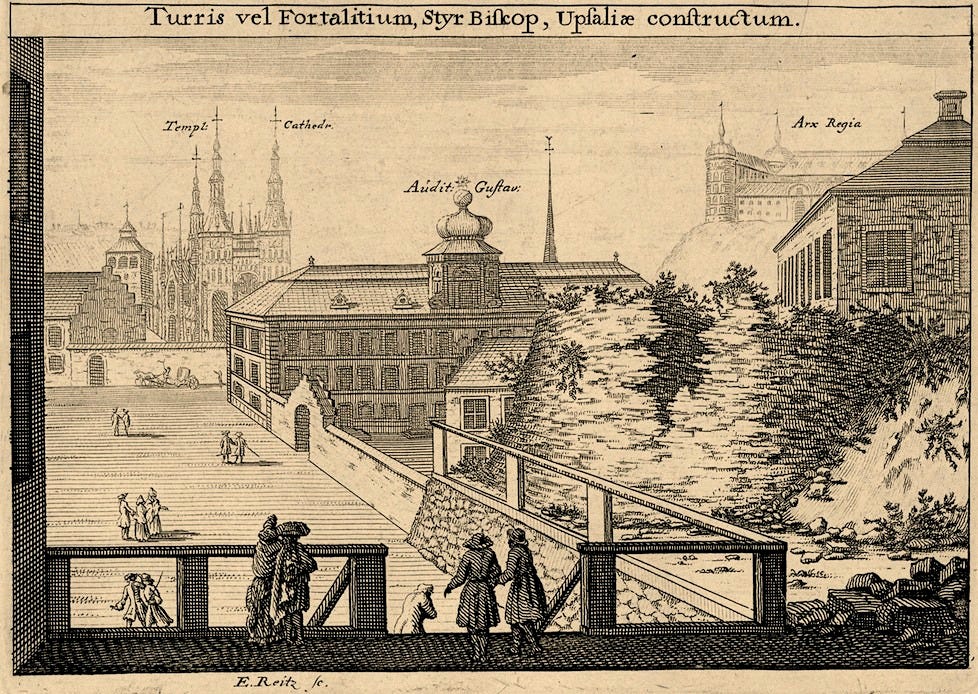

On top of the Gustavianum they spotted its origin – the outline of a man in his seventies, taking a commanding stance beneath the domed crown of the university building.

Scraps of paper spiralled around his hazy contours, bathed in amber light. Across the river, where many of the professors had their homes, collections of books, antiquities and life’s work in manuscripts had already gone up in flames.

It was also where his own house stood.

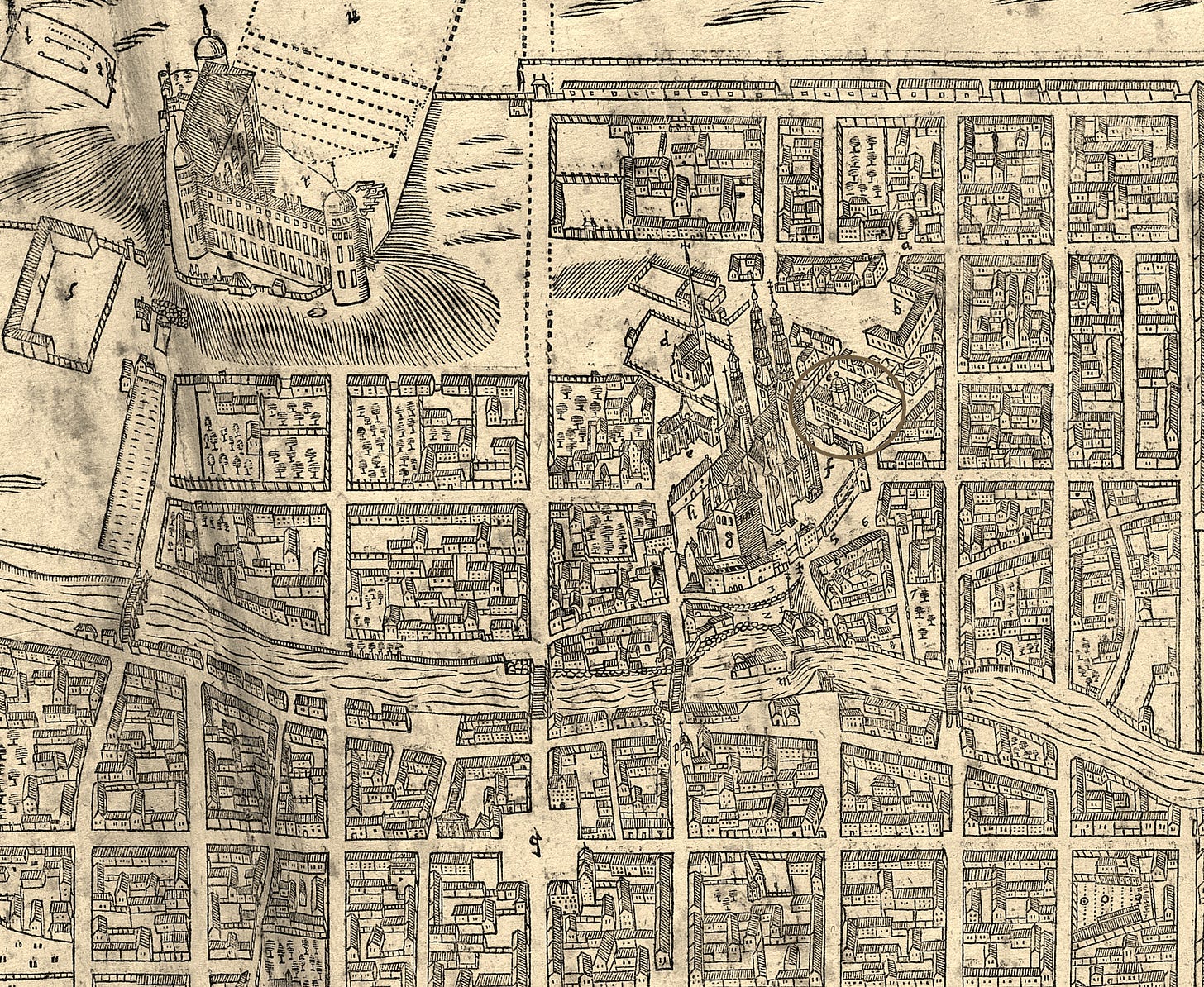

It had been in the early hours that the flames crossed the river, reaching towards the cathedral and the Gustavianum. Ten years prior, the university library had been moved into the building Rudbeck himself had designed.2 Beneath the feet of the clamouring man spread shelves filled with centuries of learning.

Supporting himself with one hand on the roof, Olof Rudbeck directed the firemen with the other hand, his hoarse voice forcing through the smoke, again and again: “Save the books!”

“Save the books!”

The Magnificent Mister Rudbeck

By 1702, the man shouting from the roof was a local celebrity. For decades, Olof Rudbeck had firmly held the reins of Sweden’s leading university in his hands.

Uppsala was the ground on which his family and his career as a professor of anatomy had flourished. It was here, in the old city with its grave mounds surrounded by a wide plain and rivers, that the polymath eventually embarked on a quest that dominated the last three decades of his life – the ancient promise made by the Greeks under the name Atlantis.

In the first volume of his Atlantica, Rudbeck argued that there was a historic truth underlying the legend told by Plato and others. It spoke eloquently about the origin of civilisation, of the gods, the alphabet, and astronomy. Their cradle, Rudbeck was certain, had stood in Scandinavia.

In the following three volumes (1679–1702) and over thousands of pages, Rudbeck elaborated his conviction. Not only was Atlantis real: the landmarks of all ancient myths and routes of epic endeavours – from the Garden of the Hesperides to the Elysian Fields, from Odysseus to the Argonauts – could be traced on the map of Sweden.

A Life’s Work in a Cabinet

In hundreds of illustrations, the Atlantica presented a vision of the North as the lands promised in Europe’s oldest myths. It was a tailor-made narrative glorifying the Swedish Empire at its peak. This sweeping vision Rudbeck underpinned with geographical maps, diagrams, depictions of antiquities and archaeological sites at home and abroad, woodcuts of plants and animals, and panoramas of mountain ranges and coastlines.

These illustrations we have made accessible through our visual database Reaching for Atlantis, and continue to tell stories behind them here on The Notebook.

Around 1700, Rudbeck’s ideas had sparked a veritable industry at Uppsala.

For decades, students had discussed (and defended) his ideas on Sweden’s earliest history in academic dissertations.3 Artists prepared woodblocks to illustrate the fourth volume of his Atlantica.

In parallel, his entire family worked towards the Campus Elysii (‘The Elysian Fields’). The mythical title designated the botanical atlas in which Rudbeck – also the founder of the botanical garden at Uppsala – pursued no lesser goal than displaying the richness of all known plants of the earth with thousands of illustrations.

In the months before May, churchgoers may have noted Rudbeck’s assistants carrying printing material into the cathedral. Among them were sheets of the Atlantica’s last and forthcoming volumes and of his magnum opus on plants, his manuscripts and printer’s copies, and thousands of woodblocks destined to illustrate their pages.

We do not know why Rudbeck entrusted this output from a decade of work to a closet not far from the church’s main portal. Yet it was there that the materialised sum of his thought lay stored, neatly stacked in a wooden cabinet next to the organ.

Final Chimes

Swathes of smoke hung over Uppsala when the sun rose on 16 May 1702. From miles away, farmers had seen the cathedral’s towers light up like torches that night, fanned by the strong winds.

Thick smoke now was pouring forth from the apertures above the clockwork.

The clock was striking nine when Rudbeck raised his view to the north tower. Moments later, the mechanism inside had melted, unleashing the hands into a race around the clock-face.

He saw the impact before he heard it. Opposite the church square, the north tower collapsed. Like a metal comet, the falling clockwork struck through the cathedral’s vault, dragging a tail of embers behind. Two hours after the rain of sparks had fallen, the hole gaping in the ceiling was still spitting smoke.

Across the church square, the Gustavianum was standing, a last bastion in the inferno. The firemen had managed to save the university’s books.

Of the cathedral’s interior, however, nothing remained. The papers and woodcuts Rudbeck had stored in the wooden cabinet were ash. A few sheets printed for the fourth volume of the Atlantica were all that could be salvaged.4

Atlantis Falling

On 16 May 1702, the mosaic of Sweden’s glorious history that Rudbeck had spent decades piecing together fell apart.

In one night, his family home, his collection of scientific instruments and antiquities were all destroyed. The botanical garden where he had cultivated specimens from across the world lay in ashes. The same fate met his notes and library, many of his own printed works, as well as the notes and collections his son had brought back from his 1695 expedition to Northern Sweden.

Weeks after the fire, farmers still found shreds of burned paper in forests miles away from the city centre.

Days after the fire, Rudbeck spoke of resilience. Yet he never recovered from the loss. The Great Fire had consumed more than Uppsala. It had consumed the stage on which he traced ancient myth and civilisation home.

Rags and cinders remained from the pieces he arranged in meaning.

A few months later, Olof Rudbeck passed away.

Further Reading and References

This account of the Great Fire builds – with some artistic license – on the narratives of Johan Eenberg, En utförlig Relation Om den Grufweliga Eldswåda och Skada, som sig tildrog med Upsala Stad den 16 Maji åhr 1702, Uppsala 1703 (online on runeberg.org), and Per Daniel Amadeus Atterbom, Minne af professoren i medicinen vid Upsala universitet Olof Rudbeck den äldre, esp. pp. 240f. (online on Google Books; modern edition in Per Daniel Amadeus Atterbom, Olof Rudbeck, Stockholm 2013).

On the full extent of Rudbeck’s ideas see the magisterial study by Bernd Roling, Odin’s Imperium: der Rudbeckianismus als Paradigma an den skandinavischen Universitäten (1680-1860), Leiden 2020.

Three sets of sheets comprising the initial two hundred pages – about a quarter of the final work – survive.