The Beard of Atlas

Following a 17th-century panorama to the Swedish mountains – resurfacing in their 21st-century reality.

Preface

In the opening minutes of Frozen Atlantis, there is a scene in which a series of mountain panoramas lies spread out on a coffee table. We are in the Åre home of National Geographic explorer Lars Larsson.

With the knowledge of a map enthusiast, Lars explains the pinpoint accuracy of the the illustrations produced by Swedish explorer Sven Hedin around 1900 – landscape views Lars himself traced through the deserts of Central Asia and the Himalayas.

That year, I had travelled to the mountains of Sweden, following an invitation by Lars to discuss a riddle from Olof Rudbeck’s Atlantica: a 17th-century panorama depicting peaks Lars had known and skied for many years.

“To be honest,” Lars admits in the film, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

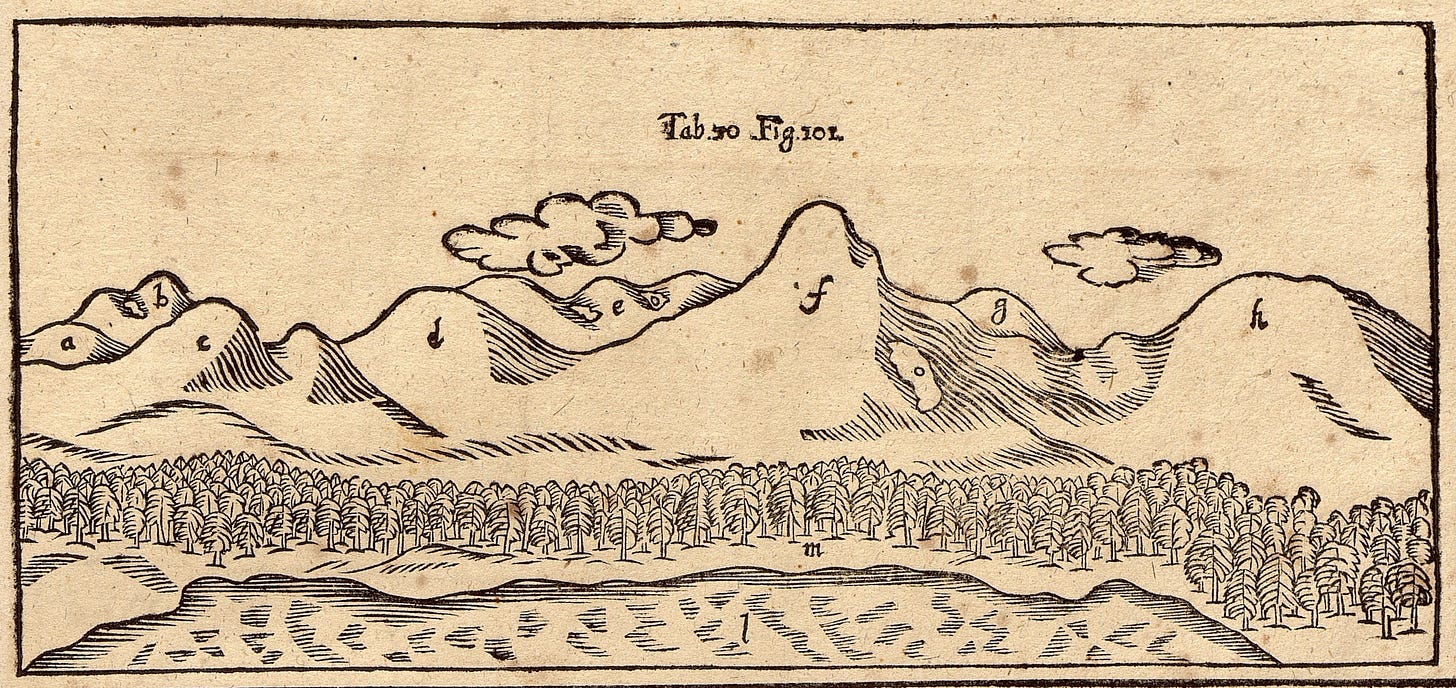

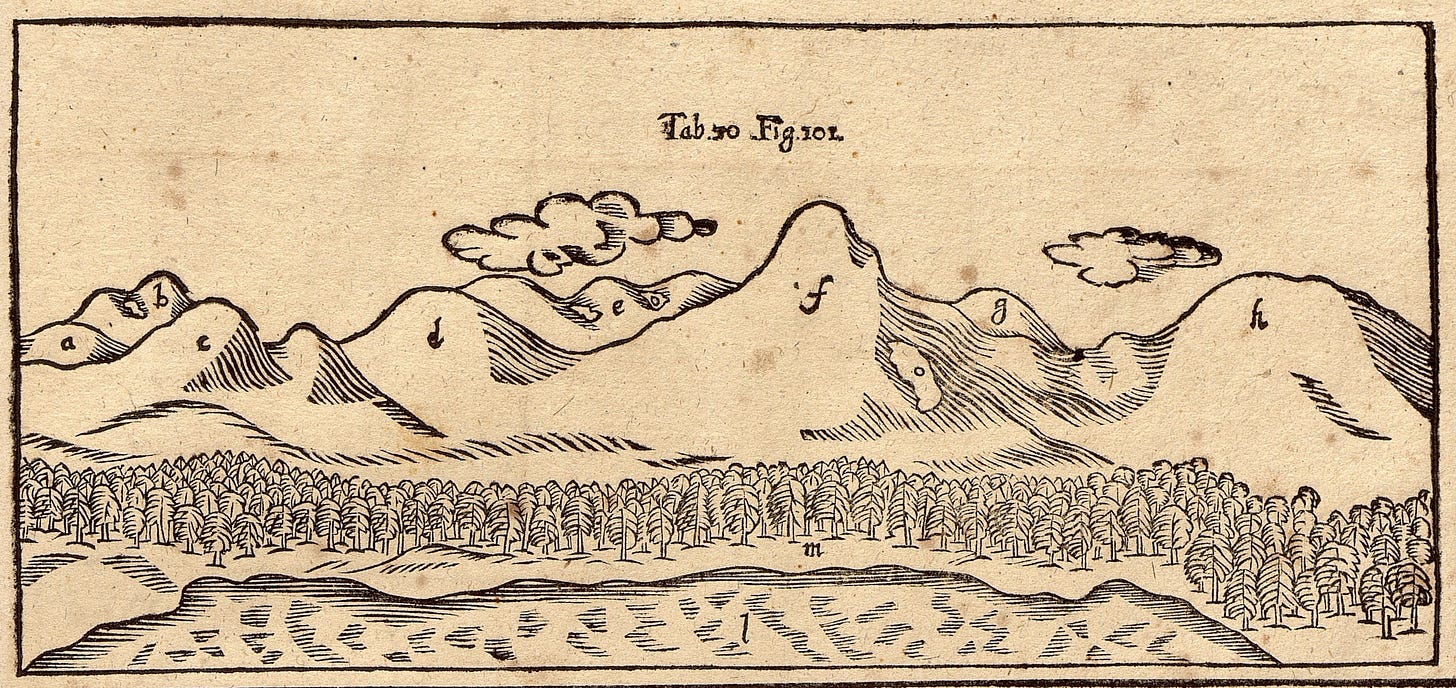

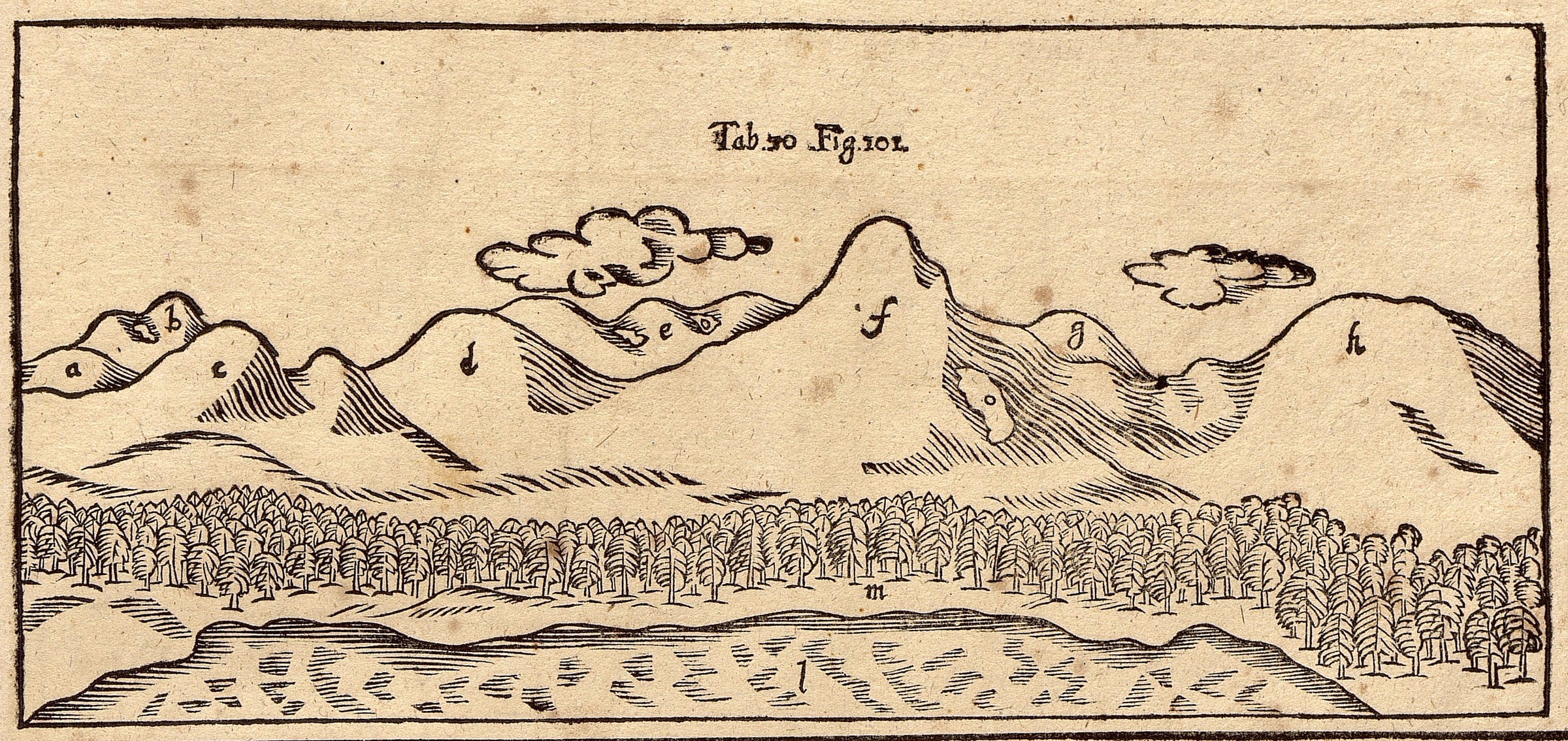

For hours, we talked about the views Rudbeck had produced in the 1670s, depicting the mountain chains of northern Sweden. I had come to Jämtland that autumn to trace the landscapes behind one of them – the second in a series of panoramas through which Rudbeck opened windows onto landscapes he charged with myth.

“That is basically what I also managed to do with this one here, from further south, at Idre,” I state in the film, echoing Lars’s method of re-photographing historic views.

In reality, however, the path to understanding the first of Rudbeck’s panoramic riddles had been more winding – a journey through shifting landscapes that planted seeds of what would later become a feature film.

I. The Elusive Panorama

I remember the moment I had given up my search for the vantage point, on a hill in Middle Sweden, not far from the Norwegian border.

In front of me, the last rays of sun filled tyre marks on the ground with shadows. On my skin, I felt the air around me growing colder.

The day was coming to an end, and I still had no clue.

In my breast pocket, I carried a printout of a 17th-century panorama, worn out after the past days in the Idre mountains. Three centuries ago, this woodcut had opened up a window into a world of stories – a world that Olof Rudbeck had charged with ancient myth.

The autumn before my journey to Jämtland, I had followed the panorama to Dalarna, to a range of humble peaks, polished by the last Ice Age.

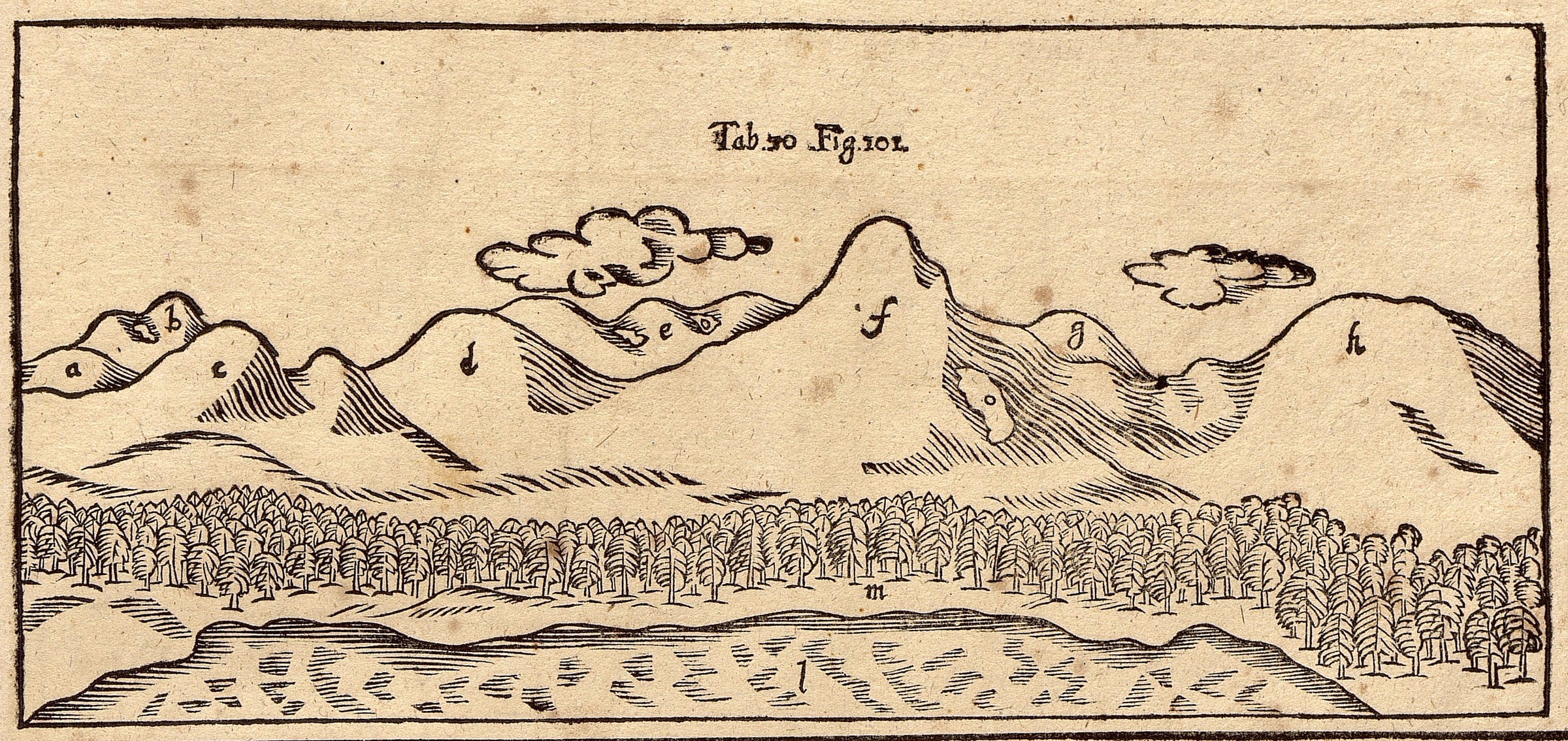

In 1675, an expedition Rudbeck sent north had travelled and drawn these mountains. The hope to see what they had seen had taken me to the southern banks of the Dalälven River (its widening waters are labelled as (l) near the lower margin).

Standing on a hilltop, I heard throaty calls carry up from the river valley – the swans whose path I had crossed before, as their wedge floated downstream underneath the Dalälven bridge.

On a gravel road I had wandered along the forest that lined the other bank of the river. Clearings opened along the path, offering glimpses towards the ski resorts of Idre and the bald peaks rising beyond.

Rags of barrier tape flapped from a few toothpick trees, the names of lumber companies barely legible on the sun-bleached plastic.

I felt my feet sink into the ground as I headed uphill, towards a treeless elevation, across a carpet of white lichen and blueberry bushes that the seasons had left in fiery red. Next to the tracks that harvesters had ploughed, fir tree saplings rose in geometric patterns from the undergrowth of what once had been a forest.

One last time, I reached for the printout in my breast pocket.

My fingers still fiddling with a stubborn zipper, I moved towards the highest point of the hill, my view eventually peeking above a screen of trees the machines had left standing. Above its veil, I beheld the Idre range, its silhouette far off from what I remembered from the panorama.

Eventually, I let go of the zipper again. This doesn’t make sense, I thought, and began to look for more even ground to spend the night.

II. Where Stories Begin: The Library

Mythical Heights: Rudbeck’s Claims

A week earlier, I had printed out the panorama I carried in my pocket from a digital copy of Olof Rudbeck’s Atlantica.

The volume of plates illustrating this 17th-century work includes a series of mountain panoramas, showing views of the main ridge that separates Sweden from Norway.1 On various occasions, Rudbeck made use of these representations of landscapes to link ancient myth to Swedish landscapes.

In the mountains and nature up north, in their shapes and names, he saw evidence that the ancient geographers, naturalists, and mythographers had meant his homeland when they spoke of the wondrous Hyperborean Mountains, the lofty Mountains of Atlas, and the pines growing on them.

In fact, Rudbeck proudly claimed, Sweden could boast no less than the highest mountains in Europe, the true counterpart to what the ancients had described under many names.

The Fight over Mythical Mountain

Among interpreters of ancient texts, such claims were far from uncontested.

“Erudite men such as Salmasius, Vossius and others,” Rudbeck complained in a letter to his protector Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie, “do not believe that our mountains are so high above sea level that they could be called the Hyperborean Mountains, of which the most ancient authors of the world have written so much.”2

Isaac Vossius was one of the intellectuals Rudbeck mentioned here. Since 1648, the Dutch bibliophile had served as court librarian to Queen Christina. He was one of the humanist heavyweights the Swedish regent had attracted to her court in Stockholm.

Among his works, Vossius counted a commentary on Pomponius Mela. The Greek author ranked among the foremost writers on geography, and he too had touched on the mythical Hyperborean Mountains. However, as Vossius stated in his commentary, all attempts to locate the disputed range in the North must be considered fairy tales, as the local mountains merely rise to humble size:

The Norwegian mountains are considered to be the highest up north, but none of them rises to two stadia of altitude.

Isaac VOSSIUS, Observations on Pomponius Mela3

For Rudbeck, this was just another misinterpretation, floated by an armchair scholar with no clue of the North. Judgements like the one by Vossius, he complained, had prevented learned men from acknowledging the foremost role his country could claim as the one and only environment that had inspired our earliest myths and stories.

The 1675 Expedition

With his Atlantica, Rudbeck aimed to end this debate once and for all.

By the middle of the 1670s, Rudbeck had delved deeply into preparing the first volume of this work. Four years before its first volume appeared in 1679, he sent out an expedition up the Dalälven. Up in the mountains where this river springs, the men procured material to correct the role Sweden had played in world history – a role that Rudbeck saw forgotten and distorted for millennia.

I am now sending out two students of mathematics at my own expense who shall travel from the Baltic Sea, where the Dalälven enters, and all the way upstream to measure the highest mountains, in order to see how high our mountains are ...

Olof Rudbeck, Letter to Chancellor De la Gardie (1674) 4

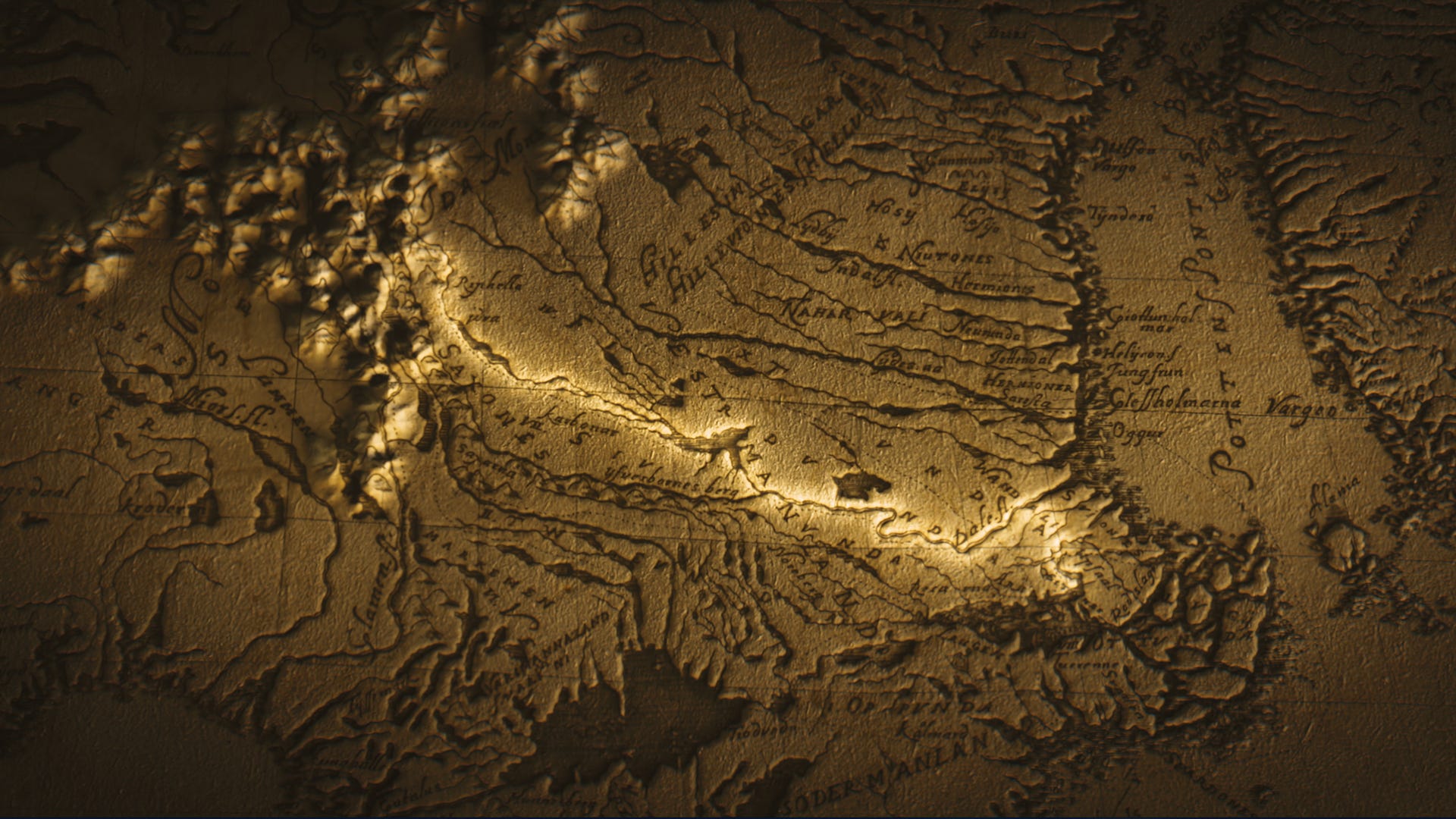

The Dalälven marks the border to Norrland, a name traditionally used for the northern part of Sweden. In the summer of 1675, Rudbeck’s men travelled upstream, towards lands the Crown had (re)gained with the 1645 peace treatise of Brömsebro.

From the Swedish-Norwegian border mountains, they returned with a rich harvest. In Uppsala, Rudbeck drew on their maps, mountain measurements, and panoramas to rewrite the history of Sweden.

The Harvest from the North

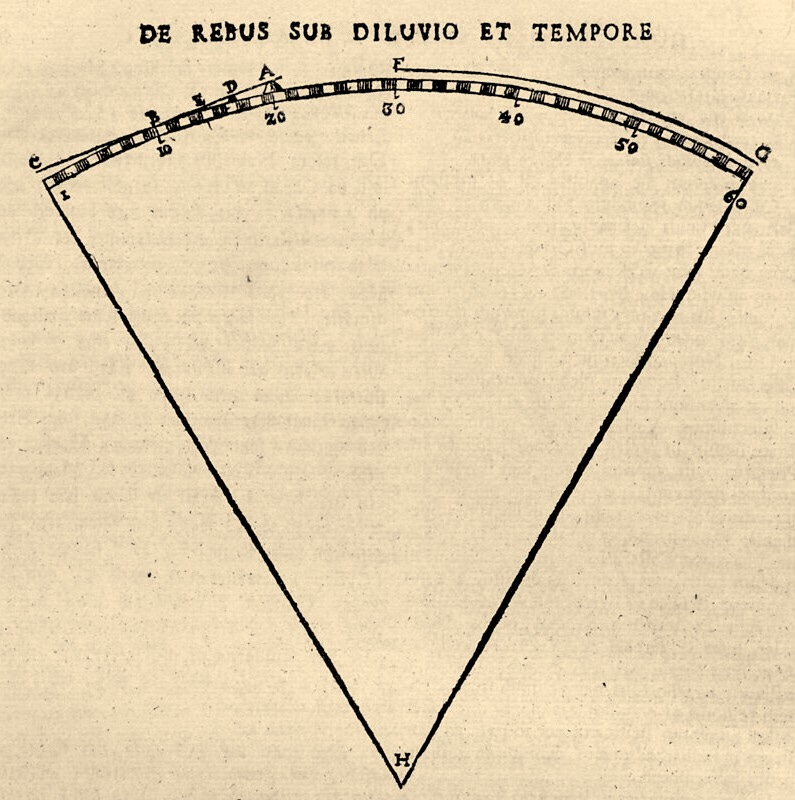

At his desk, Rudbeck connected the measurements his students had taken of peaks near Idre and further north in Jämtland with calculations he produced on the levels of waterfalls further downstream, tracing them down to sea level. On this basis, he concluded that the top peaks of the main ridge must at least be ten times higher than the maximum altitude Vossius had claimed (2 stadia, approx. 360m).5

Rudbeck’s numbers elevated Sweden’s peaks above those considered the highest in Europe at the time. Yet the meaning of numerical claims was eclipsed by their historical implications.

As Sweden owned the highest mountain, Rudbeck argued, this put his country first when it came to tracing from where the earth was repopulated after the Biblical Flood. Where the mountains rose highest, he elaborated, land first emerged again in Europe. So it must have been here in the North, he concluded, that Noah’s son Japheth found first land as the waters began to recede.

Atlas Slabbed – The Myth According to Ovid

The implications of the expedition material extended far beyond the biblical narrative. A signature claim of Rudbeck’s work was that the legendary island Atlantis identified as Scandinavia.

In his Critias, the Greek philosopher Plato relates that the god of the sea had made his first-born son the first king of the island called Atlantis (Greek for ‘of Atlas’).6 As namesake of the island, Atlas came close to a patron of Rudbeck’s Atlantica itself.

In the work, Rudbeck had a closer look at the myths about this god who had lent the island and its central mountain range his name. In his Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid tells a story of how the mountains carrying Atlas’s name came into being. The episode is embedded in the tales of Perseus, the hero riding a winged horse.

In the fourth book, Perseus had just slain Medusa, the horrendous Gorgon whose head hissed with snakes, and whose glance turned everything to stone. Riding away in the air victoriously, the hero carried the Medusa’s petrifying head safely in a bag, her cheeks pale as the last drops of blood dripped out in flight, and her eyes still filled with fright.

Yet the triumph did not last long. Conflicting winds, Ovid tells, hurled the hero across the globe, making him a castaway on remote shores.

The sun god’s horses were already hastening towards their cradle when he landed at the realm of Atlas, keeper of the Garden of the Hesperides and their far-famed Golden Apples.

“A son of Jupiter asks for shelter for one night,” Perseus approached the imposing ruler of these lands, “and I come with a good story or two!”

His words made Atlas wince. From a secluded place in his memory, an oracle flared up that he had received far back in time. “There will come a time”, its words had warned, “when Jupiter’s son will near your realm, set on wrestling the golden apples from your garden”.

The Titan’s face turned cold.

“Keep your made-up stories to yourself and leave,” Atlas said and clenched his fist, “or your ancestry will be of little avail!”

Rebuked by the imposing giant, Perseus budged, and his left hand reached for his bag.

“Take this present then from the guest you spurn!” Perseus exclaimed. Turning his own eyes towards the ground, he brandished the Gorgone’s head against Atlas:

His hair and beard were changed to trees,

his shoulders and arms to spreading ridges;

What had been his head was now the mountain’s top,

and his bones were changed to stones.

Then he grew to monstrous size in all his parts

– for so, O gods, ye had willed it –

and the whole heaven with all its stars rested upon his head.Ovid, Metamorphoses, 4.657-62 7

Tracing the Beard of Atlas

Ever since the clash with the titan, Ovid concludes the myth, a sky-high mountain loomed over Atlas’s realm. His Metamorphoses tell a story of how the Atlas Mountains came to being and their mythical height – a range as large as the god himself once was – as well as the forests created from his rugged beard.

Traditionally, the majority of humanists who interpreted Ovid’s mythical geography had located the Atlas range in Northern Africa. Yet in his Atlantica, Rudbeck argued that there was another Atlas range up north.8

For him, this name was simply one among the many synonyms by which ancient writers had referred to the mountains dividing Sweden and Norway.

When his expedition returned in 1675, the mountain panorama from Idre and their reports provided Rudbeck with new evidence. Up north, he argued, the treeless top of Mount Städjan – seen at the center of his panorama (f) – perfectly corresponded to the bald head of Atlas of which Ovid had spoken. And so did the forest at his foot (m), in which the poet had, in Rudbeck’s interpretation, seen the transformed remnants of Atlas’s Beard.

An anthropomorphising view on the Swedish mountains lay behind the myth that Ovid still remembered, Rudbeck concluded. From his library at Uppsala, he presented further evidence to sustain this view. Manuscripts he consulted, Rudbeck relates, showed a wider image tradition connected to the theme of bearded-god-turned-forested-mountain.9

Taking Bearings with Vergil

In the texts of other writers, there still was evidence to be found to connect Atlas to the north. Among these authors counts the Roman poet Vergil.

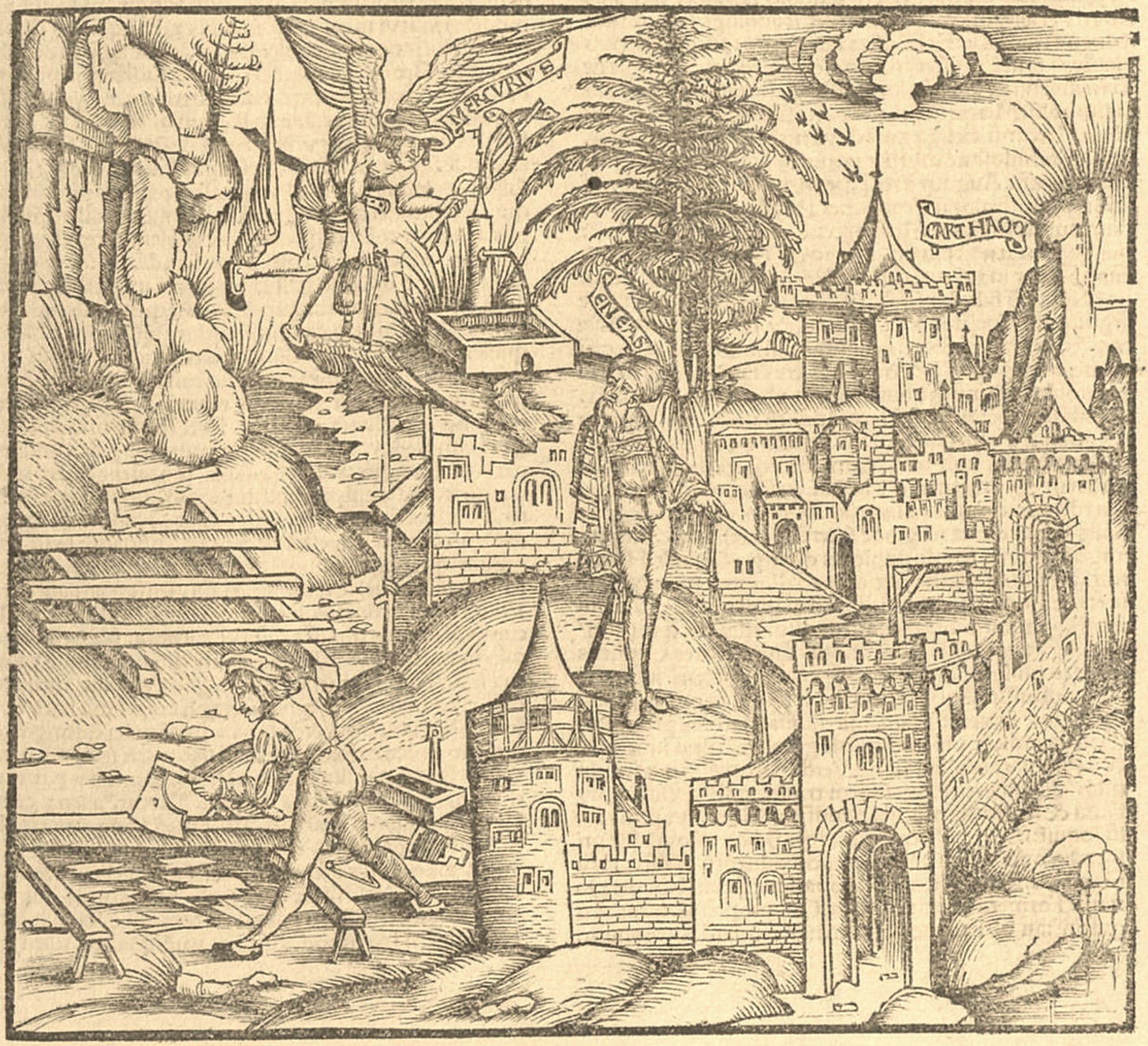

In his epic the Aeneid, Vergil tells of the journey of Aeneas, a refugee from Troy who stranded in Africa on his way to Italy. Reaching Carthage, Aeneas falls in love with Queen Dido. Soon, the divine plan behind the hero’s journey (the foundation of Rome and the beginning of the Julian family) runs danger of stalling.

Fearing for its fulfilment, Jupiter immediately mobilises his divine messenger. From Mount Olympus, Mercury sets out with a clear brief: Travel to Carthage, and bring the enamoured hero back on track!

As Mercury soars into the air, Vergil writes, Mercury turned to the pine-covered Mount Atlas, to take his bearings on the cloud-veiled peak as do the migrating birds:

Soon in his flight he saw the steep flanks

and the summit of strong Atlas,

who props the heavens with his head;

Atlas, whose pine-covered crown is always wreathed

in dark clouds and lashed by the wind and rain:

Fallen snow covers his shoulders,

while rivers drop from the old man’s chin,

and his rough beard bristles with ice.VERGIL, Aeneid, 4.346–51 10

Unlocking the Pines of Atlas

For Rudbeck, Vergil’s passage distinctively reeked of Sweden’s North.

Regarding the ‘rivers dropping from his chin’, he argued, all of the country’s Big Rivers spring from the same mountain range, as his maps outlined.11 As for the ‘fallen snow covering his shoulders’, his expedition had testified that these could even be seen in summer (in fact, the panoramas he printed in the Atlantica showed fields of snow dotting the mountain range, see letter (o) in the illustration above).

The ‘pine-covered crown’ from Vergil’s description particularly piqued the curiosity of Rudbeck, the man who had started the botanical garden at Uppsala.

There were ancient authorities who had written more about the fauna on Mount Atlas. Among them was the Roman writer Pliny. In his Natural History, he confirmed this mountain as covered in snow even in summer – just as Rudbeck’s expedition had experienced. Its top he described as filled with dense and lofty forests of trees of an unknown kind, similar to the cypress.12

Sifting through illustrations of conifers in the later volumes of his Atlantica, Rudbeck zeroed in on the slim Swedish spruce as the only candidate that qualified. Its form, he claimed, was perfectly adapted to the heavy snowfalls of the true Atlas mountains. It was this tree, he concluded, that perfectly ticked all the boxes of Pliny’s description, emerging as the only contender for the ‘pine-covered crown’ that Vergil mentioned.

Time and again, the Atlantica confronted readers across Europe with a central claim: After millennia, Sweden’s nature still held the keys to advance to the core of ancient myth. In his home country, Rudbeck claimed, the gates to this truth stood open for all to see – to experience an all-encompassing epiphany with all senses.

And so I had left for the North, a printout of Rudbeck’s mountain panorama in my pocket.

III. Audience with Atlas

Arriving North

“Welcome to Himmelfjäll”, the billboards passing by the bus windows read. “Snow guarantee from 21 December until 19 April.”

At the end of the aisle, red LEDs announced the next stop: Idre Fjäll.

With a hissing sound, the rear door opened. From the bottom of the steps, a crisp autumn breeze cut through the overheated air.

It was off-season, and I had been the only traveller that morning in late autumn. Stepping out onto an empty parking lot, my gaze wandered across the concrete expanse. At its end, snow cannons parked on stilts, the wind moving idle fans inside.

Vans of carpenters and plumbers parked in the driveways I passed on my way to the first outlook I wanted to test into the mountains. Plastic foil still covered window cutouts in the cottages. The year before, a new skiing resort had opened in the Idre mountains – the first in Sweden within the past three decades.

A swathe in the forest led uphill, lined by lift pylons. Wrapped around their concrete bases, paddings flashed in factory-fresh red colour. To their side, a dugout for the snow lances, with excavator bites still along its rim.

At the top of the hill, a gravel-clad plateau widened, furrowed by the tracks of Caterpillars. Button seats dangled over my head as I sought orientation in Rudbeck’s mountains. I had ventured into the panorama, presumably standing somewhat left of the peak marked as (d).

A few glaring dots drew my attention to a neighbouring hill. White surfaces reflected rays of sun that made it through the overcast sky. Near the top of the ski pistes, tons of snow awaited the coming season under plastic foil.

For a moment, I thought Vergil’s lines on the snow on Atlas’s shoulders, and the fields of snow which Rudbeck’s men had still reported even in summer. Here in northern Dalarna, such sights have become a thing of the past.

The panoramas of the ski resorts I saw along the way present a winter vision unaffected by recent change. In one of them I spotted the names of gods that featured in the ancient myths – Neptune (the father of Atlas), or Mercury, the divine messenger. Near the feet of ski pistes, their mythical names shed lustre to clusters of freshly built chalets.

Yet that winter idyll of the touristic panoramas is fading on the margins. There are already entire months without snowfall during winter in Northern Dalarna. Until the middle of this century, the average length of the winter season in Sweden’s skiing resorts is estimated to shrink by twenty days.13

Trees Beyond our Sense of Time

For the night, I hiked into the forests that spread around Städjan, the mountain at the center of Rudbeck’s panorama (see ‘f’ above).

Städjan means ‘anvil’ in Swedish, its profile dominating the view of the wider range. With 1131m above sea level, the peak as measured today falls somewhat short of the rank to which Rudbeck raised it among the highest mountains of the world.

The first sun rose fragrances of earth and fungi rose from the sponge-like ground which absorbed my steps towards Städjan’s top the next morning. Silvery stumps and logs pierced the carpet of moss, lichen, needles, and blueberry shrubs.

Above my head, black streaks of tagellav-lichens wavered in the wind like wisps of a primeval creature caught in the conifer branches. In the distance, the hammering of a woodpecker.

Today, 24.500 hectares around Städjan are designated as nature reserve, integrated into the Natura 2000 protection scheme. Trees are left to grow and die undisturbed. When they fall, their wood remains part of the forest, providing habitats and sustenance for trees, plants, lichen, mushrooms, microorganisms, mammals, birds, and insects.

Some two hundred meters below the top of Städjan, the Beard of Atlas thins out. Under the climate conditions of 1900, the forest ended further below.

Further up, a few crooked still shrubs dot the treeless ground of the fjäll, a vegetation already described by Carl Linnaeus in his Dalaresa (‘Voyage through Dalarna’). When the young botanist climbed Städjan in 1734, he noticed the low brushes that hugged the slopes above the tree-line in the form of roots grown into the earth.14

Many of these shrubs are stunted spruces. Cowering near the ground, they have weathered the storms, snows, and forest fires that assail Northern Dalarna for centuries, some even for millennia. A precious few of them are in fact old enough to have seen the last Ice Age recede.

With temperatures rising, many of these veteran trees now have started new offshoots.15 Among them ranks the so-called Linnégranen (‘Spruce of Linnaeus’), whose roots biologists in recent decades could date to 4420 years, or the oldest tree in the world in the neighbouring Fulufjället.16

In Rudbeck’s imagination, such ages led towards (or even beyond) the beginning of the chronological charts printed in his Atlantica, to times when he believed the waters of the Deluge to have first receded from the world’s highest peaks, and when Japhet arrived to Sweden’s mountains to re-settle Europe – an event that in his view marked the outer margin of imagined time.

The Values We See

A stiff wind scraped the top of Städjan. Leaning into it, my eyes followed the spot lights which fell through holes in the overcast sky, on the forests that had followed the ice line as it receded millennia ago.

The wandering shafts of light illuminated the expanse in which the Dalälven River shimmered like a band of mercury. In steady rhythm, patches of brown lit up in their lustre cones.

A front line becomes visible from the top of Städjan. Clearcut areas and ski pistes adumbrate where the nature reserve surrounding the peak ends.

The stakeholders in this area are many – tourists and tour operators, environmentalists and biologists, the Sámi community who herd their reindeer in the forests, investors, the owners of cabins and historic farms, municipalities, and skiing resorts. Not too long ago, there were debates on building lifts on Städjan itself.

How do we define values, and where do we draw the line?

When the reserve was declared, “nature types uninfluenced by man with a natural set of species and ecological function” played a decisive role.17 The work of biologists, researchers, and artists has widened our understanding of interconnectedness between trees, plants, lichen, mushrooms, microorganisms, mammals, birds, and insects, and deepened our sense of awe.18

In habitats left undisturbed, life grows in interdependency. The lichen hanging from the trees and feed the reindeer in wintertime. After a clearcut, they take almost a century form anew. Others of these systems that sustain life are, if destroyed, next to impossible to re-create. And many of them may still lie beyond our grasp.

Curtailing Awe

Historically, clearcutting was considered a sustainable as well as a social practice in Sweden. Among the largest forest owners are state-owned companies. For a long time, the narrative held sway that forests cut and replanted in the north helped build schools and light hospitals elsewhere in the country.

In 1993, the Swedish government further liberalised forest laws. Since then, responsibility has largely resided with landowners, bound primarily by principles such as ‘frihet under ansvar’ (‘freedom bound by responsibility’) and ‘allmän hänsyn’ (‘general consideration’).

Clearcuts must formally be announced, and a few thin alibi trees left standing as landing poles for birds.19 Such measures may be carried out only after biodiversity checks. As part of this, state officials create an inventory, assessing forest life in a specific hierarchy of values.

If the authorities do not complete this complex work within six weeks, land owners are free to proceed. In practice, 96 percent of clearcuts occur without any prior examination.

Wood plantations have replaced the majority of ancient forests in Sweden. Storytellers, filmmakers, artists, and activists are raising awareness for the complex and awe-inspiring ecosystems that are at stake – for forests that took centuries to form and cannot be recreated.

This holds particularly true for the High North, where ecosystems take longer to form and recover. Saplings re-planted today may never grow to full size as soil and climate conditions change in the coming decades – and may never again capture the atmospheric carbon dioxide once stores in those trees.

Yet beneath all the so-called ‘services of forests’ marshalled by scientists in their defence lies a deeper layer – the meanings we find in them; the way they root us in a world of which we feel part of.

The ancient myths that Rudbeck connected to the forests at Idre illustrate this palimpsestic process by which we inscribe the world with stories. The stories we tell define how we connect to the world around us, the value we grant it, the care we feel for it.

The forests around us store them too, layer upon layer – the stories of who we have been.

As I descended Städjan through ‘The Beard of Atlas’ ebbing from its slopes, I passed a pocket with giant trees. When Rudbeck’s expedition neared the mountain in 1675, some of these trees had still been saplings.

Close to the veteran trees, the forest ground bulged with stumps overgrown with moss – the remains of trees that took centuries to grow and several men to embrace. The tallest of them did not survive to the present day.

In the decades of dimensionsavverkning around 1900, loggers hiked up and skimmed the forest.20 Floated down the Dalälven, their stems would serve as beams in railway bridges.

IV. Epilogue

It had been a historical mountain panorama that first led my way to Idre. Yet during my days of wandering through the mountains, the 21st-century reality of the forests up north had pressed against the mythical frame through which I sought to see these lands. On a clearcut along the Dalälven, I eventually gave up the search to find the original vantage point of Rudbeck’s Idre panorama.

A few weeks later, I found myself up on the threshing floor of an artist’s barn. On the Hallnäs Peninsula on the Baltic Sea, a young couple had turned the family farm into a retreat for artists, some two hours north of Stockholm. A few houses, painted in Falun-red, nested in a forest flaring up with yellow birches.

Autumn had reached the south, and through a half-open square window, the wind carried scraps of sound from distant waves. A few kilometres from here, the Dalälven reaches the Baltic Sea.

The evening sun poured over the notes from my journey, illuminating grains of dust as they passed through a lustre cone of late September light. From my backpack, I heaved a leather-bound volume onto the desk that I had borrowed from the library at Uppsala.

In the work by Karl-Erik Forsslund, I travelled upstream one more time.

More than a century ago, the Swedish Romanticist had embarked on journeys along the Dalälven River. In the years around World War One, he published the first parts of his ‘With the Dalälven from its Sources to the Sea’.21

In this work, Forsslund unfolded a vision of pristine lands upstream along the river, recounting days of travel and nights spent under summer skies, or as a guest of farmers whose homes and dresses he photographed and whose songs he printed, like invaluable relics endangered by forces luring further downstream.

Forsslund described his journey as a journey back in time, leading through all ages of human development: from the smoke-belching factory chimneys near the coast to the farms of Dalarna, a region in which Forsslund (as did the painter Anders Zorn) found resonance as a contrast to the industrialising cities. Upstream, he believed to have encountered humankind’s first state as nomads, which he associated with the Sámi who live in the mountains, where the Dalälven has its springs.

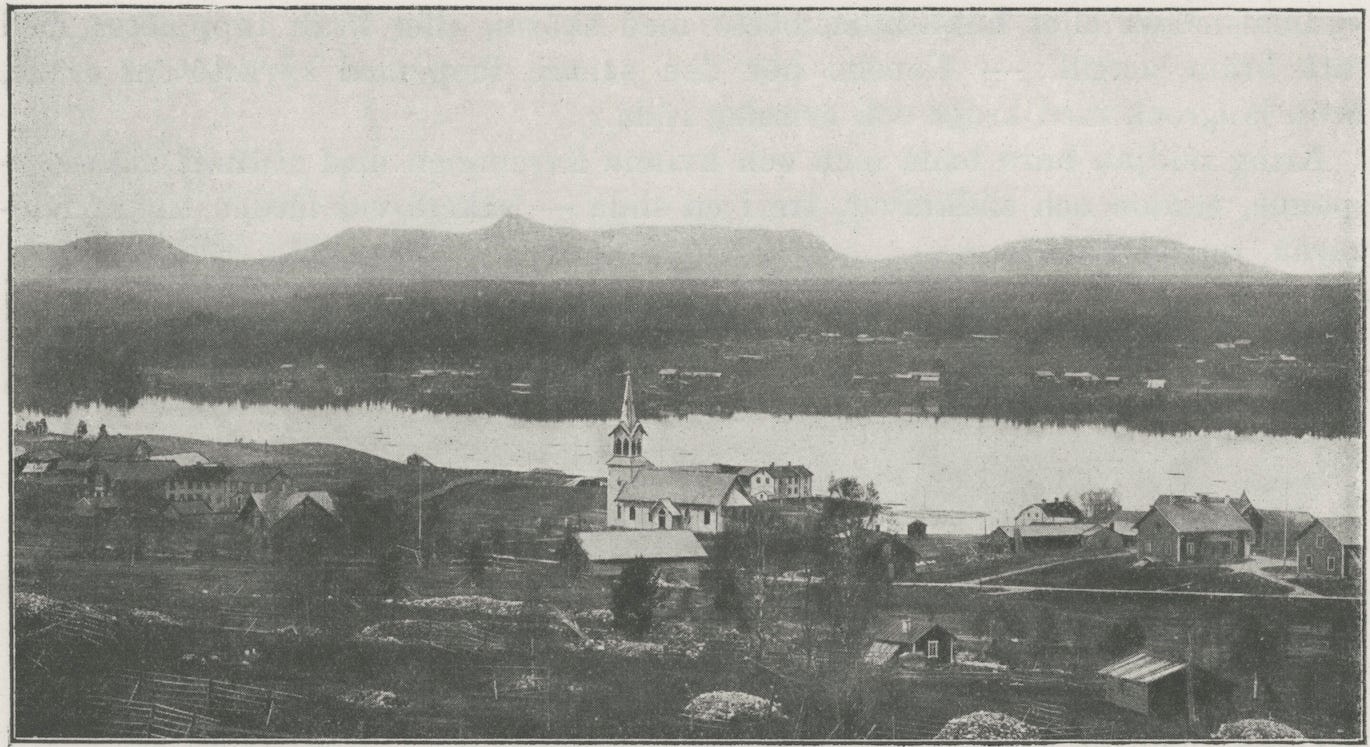

Leafing through Forsslund’s pages, I travelled downstream again, passing the peaks that I had left behind around Idre. At a photograph showing the church at Särna overlooking the Dalälven, I paused.

The silhouette beyond the steeple.

The proportions were more humble. Yet clear as iron sights, the peaks on the horizon aligned around Städjan, matching the view in Rudbeck’s panorama.

In a single moment, everything fell into place.

What Rudbeck described as ‘lake formed by the Dalälven’ in the Atlantica (‘l’ in the panorama) had never been the river that widened near Idre.

It was the same river that widened again, some thirty kilometres further downstream.

In reality, the area between the water and the mountains covered by the ‘Beard of Atlas’ (‘m’ in the panorama) expanded across dozens of kilometres. I had been misled by the ways Rudbeck’s draughtsman had conveyed proportions and distance.

Leaning back into the chair, I folded my hands behind my head and stretched my shoulders. Grains of dust danced in the light of the desk lamp.

I had searched too close to the mountains to see this view emerge, the insight sank in. Yet instead of a window into a world once seen in mythical light, I had found something else up north – an environment that told of stories losing their roots.

Reaching for the light switch to call it a night, my view passed over the mountain silhouette on the photograph one last time. With the back of my hand, I wiped over the page to remove some grains of dust.

The specks stayed. And then I realised.

The photograph showed the forest harvest floating down the river, towards the sawmills in the south.

Upstream, the plucking of Atlas’s Beard had begun.

Further reading and references

All translations and photographs are my own unless stated otherwise.

Acknowledgments

I have to thank Lennart Bratt for his support in the field and the insights he shared with me. Further thanks go to Åsa Norling, Peter Sjökvist, Sven Widmalm, and Maria Ågren.

Coverage

In recent years, the topic of deforestation in Sweden has attracted coverage in international newspapers, see for example:

Marcus Westberg, “‘Forests are not renewable’: the felling of Sweden’s ancient trees”, The Guardian, 14 April 2021 (online here).

Richard Orange, “Sweden’s green dilemma: can cutting down ancient trees be good for the Earth?”, The Guardian, 25 September 2021 (online here).

Greta Thunberg, Lina Burnelius, Sommer Ackerman, Sofia Jannok, Ida Korhonen, Janne Hirvasvuopio, Jan Saijets, Fenna Swart, Anne-Sofie Sadolin Henningsen, “Burning forests for energy isn’t ‘renewable’ – now the EU must admit it”, The Guardian, 5 September 2022 (online here).

Alex Rühle, “Radikahlschlag”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14 June 2023 (online here). https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/25/swedens-green-dilemma-can-cutting-down-ancient-trees-be-good-for-the-earth

Alex Rühle, “Das Verschwinden der Wälder”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 23 Juni 2025 (online here).

Director Peter Magnusson treated the topic in his 2021 film Om Skogen (96min).

Activist groups in Sweden such as Skydda Skogen (‘Protect the Forest’) and Skogsupproret (‘The Forest Rebellion’) fight against deforestation and the colonial approach that their own country practices in the North and on Sámi territories.

In Sweden, the voices against clearcutting have become louder and reached public institutions. In 2023, for example, Uppsala University declared to abstain from clearcutting at least in parts of the large forest areas (some of them nature reserves) that have historically been managed by the institution (see press release on uu.se from 20 February 2023).

Please note the general bibliography available here.

See note no. 4.

Isaac Vossius, Observationes ad Pomponium Melam de situ orbis, The Hague 1658, pp. 106–7: “Norwagici montes omnium qui sunt in septentrione altissimi esse creduntur, attamen illorum nullus est, qui ad duorum stadiorum perpendiculum assurgat.” (digitised by Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München). The original passage from Pomponius Mela is lib. 1, cap. 19.

See the full passage in the letter by Olof Rudbeck to Chancellor Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie (15 July 1674), printed in Bref af Olof Rudbeck d.ä. rörande Upsala universitet, ed. Claes Annerstedt, vol. 2: 1670-1679, Uppsala 1889, no. 30, p. 97 (online at KB):

“Eliest wadh mit wärk anlanger så går dett nu Festina lente, ty iagh har ännu ej bekommmit de medel H. K. Maj. migh nådigast där till gaff. Och än då är iagh så pickhågat til at altidh nogot göra til min fäderneslands och public tienst att iagh nu sender 2 Mathes. studiosos på min omkostnat som skola resa ifrån Östersiön där Dalelffvan inlöper och henne alt up til högsta fiellarna affmeta att se huru höga wåra fiellar äro, emedan de lärda såsom Salmasius, Vossius och andra ei tro att wåra fiellar så höga äro mot haffvet att de kunna kallas Hyperboreorum Montes som de äldraälste i wärlden hafva så mycket skrifit om.”

The journey was scheduled for 1674, however left only the subsequent year.

Rudbeck’s addition results in 9135 cubits, ca. 26 stadia.

Cf. Plato, Critias, 114a.

After Ovid, Metamorphoses, tr. Frank Justus Miller, Cambridge (Mass.) 1921, 4.657–662: “nam barba comaeque / in silvas abeunt, iuga sunt umerique manusque, / quod caput ante fuit, summo est in monte cacumen, / ossa lapis fiunt; tum partes altus in omnes / crevit in inmensum (sic, di, statuistis) et omne / cum tot sideribus caelum requievit in illo.” (online at wikisource.org).

See e.g. Rudbeck, Atlantica, vol. I, pp. 340–46, 352–57, 566; vol. II, pp. 77–85.

Unfortunately, I have not been able to identify the manuscript source of the images printed in the Atlantica.

After Vergil, Aeneid, 346–51: “iamque volans apicem et latera ardua cernit / Atlantis duri caelum qui vertice fulcit, / Atlantis, cinctum adsidue cui nubibus atris / piniferum caput et vento pulsatur et imbri, / nix umeros infusa tegit, tum flumina mento / praecipitant senis, et glacie riget horrida barba.”

See Pliny, Natural History, V.1.

This is an estimate by the Swedish Meteorological Institute, see Mats Ekdahl, Snöns histora, Stockholm 2019, p. 71.

See Carl Linnaeus, Dalaresa, Stockholm 2024, p. 64: “Ovanpå berget, vid pass 360 alnar högt, var ett konvext ampelt fält, bart från träd och buskage, förutan att några små frutices fingo över jorden den form, som dess rötter under jorden, det är vuxo in vid jordens superficies, att dess grenar liksom ville gömma sig under jorden.”

See Lisa Öberg, Treeline dynamics in short and long term perspectives. Observational and historical evidence from the southern Swedish Scandes, Sundsvall 2010 (online at Diva).

A first introduction to the veteran trees of Sweden is provided by Lisa Öberg and Leif Kullmann, Fjällens urgamla granar: en faktabok, Östersund 2013 (see pp. 30f. for Linnégranen).

See the argumentation in “Revidering av beslut samt skötsel- och bevarandeplan för Städjan-Nipfjällets naturreservat i Älvdalens kommun”, published by Länsstyrelsen Dalarnas Län, decree from 21 Dec 2020 (511-10003-2018), p. 3: “Städjan-Nipfjället utgörs av i huvudsak av människan opåverkade naturtyper med naturlig artsammansättning och ekologisk funktion.”

See Dacher Keltner, Awe. The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How it Can Transform Your Life, New York 2023, pp. 136–8.

See the article by Erik Hoffner, “Sweden’s Green Veneer Hides Unsustainable Logging Practices”, Yale School of Environment, 01 December 2011.

On the history of the local forests see Kurt Alinder, "Särna- och Idreskogarnas historia under svensk tid. Ett bidrag till deras rätthistoriska utveckling", in: Särna – Idre 300 år. En hembygdsbok, Särna 1945, pp. 103–36.

Karl-Erik Forsslund, Med Dalälven från källorna till havet. Med över 4000 illustrationer och talrika planscher, Stockholm 1918-39.