The Stone in the Green Valley

From a furrowed rock in Patagonia to an enigmatic stone in Sweden’s North – a journey tracing how we project meaning.

Part I: Inception

The net of lines caught my eye on a snowfield.

In the Southern Andes I had climbed the Loma de las Pizarras. At the top of this ridge, a day-hike away from El Chaltén, I wanted to gaze at the spindle of vapour turning from Mt FitzRoy – the banner cloud unfolding from the peak the Indigenous called ‘The Smoking One’.1

I had noticed the furrowed stone on the way down from the peak. And it had felt as if the grooves spanning across its face kindled that instinct known from since childhood, which lets us lift our eyes to the clouds and discover shapes and patterns – as if these weathered cracks, too, held something to be read – or at least a trace to those who tried.

To The Paper Trail

The stone left me with an association leading to a memory as blurred as the cloud I had watched billowing across Patagonian skies.

The loose thread led me back to notes I had taken a few years before, at a time when I was skimming through shelf meters of historical dissertations in the Special Reading Room at Uppsala.

One of these Latin booklets contained the illustration of a stone whose faint imprint still lingered in my mind. The foldout, however, was not included in the few reproductions online at the time.

The next day, a phone photograph arrived from my friend Peter, a rare book curator at the library. While passing the shelf of 18th-century dissertations that morning, he took the shot from the 1733 booklet – an illustration that would lead me from the Andes back to the archives, into a trail of antiquarian investigation across centuries.

Part II: The Antiquarian Trio

Tracing a mysterious stone near the Norwegian-Swedish border and the legends attached to it, as documented by early Swedish antiquarians. An uncommented print of it emerges alongside a hand-drawn sketch, connected to an expedition Olof Rudbeck sent to the North in 1675.

Renhorn’s Remembrances (1733)

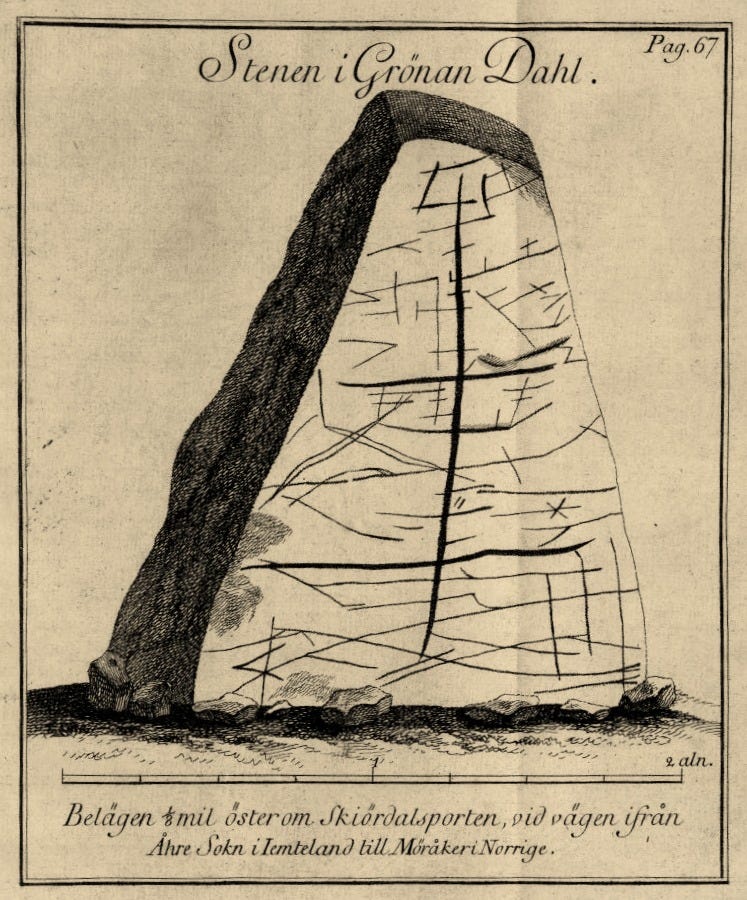

In his 1733 dissertation, Johan Renhorn revisited a stone located on the border of his home province of Jämtland in the North of Sweden.

Its face, he writes, was marked with characters veiled in mystery. At length, Renhorn recounts the works of those who had made the characters (which he had printed as a fold-out illustration) speak: of a prophecy echoing in Swedish ears from ancient song. Found in runic script on a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’, it spelled out warnings to humankind in plain daylight. They had neglected the writings of the ancients, the prophecy complained, and deviated on their path ever since, eventually provoking an upheaval of social order and the collapse of the known world.

According to this legend, the stone stood between Norway and Jämtland. Still standing, it had witnessed the world fall apart as humankind turned away from its face inscribed with runic script.

That was until everything collapsed, and the stone eventually tipped over.2

Rudbeck’s Patterns (1679)

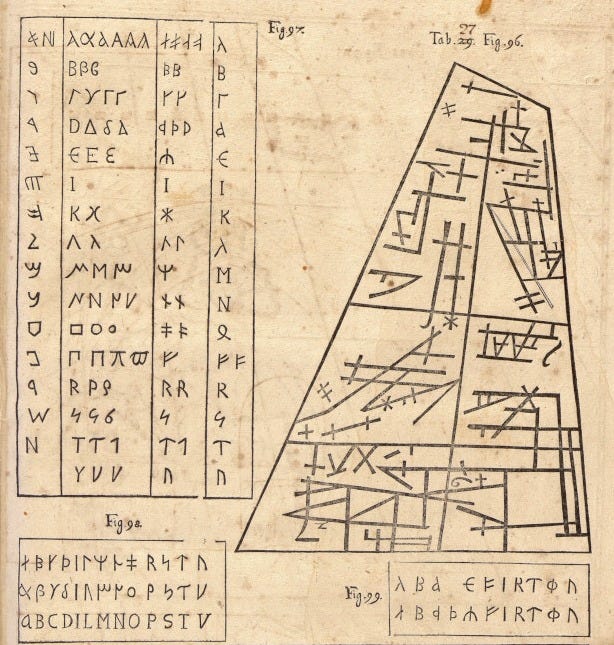

Seeing the illustration in Renhorn’s dissertation again brought another image to mind. A similar diagram featured in the volume of plates that accompanied Olof Rudbeck’s Atlantica.

The work by the Swedish polymath (1630–1702) included hundreds of illustrations which I had begun to study more closely at the time.3 The diagram counted among the ones I had logged as ‘mute’ in my memory. In his volume of plates, he placed the stone next to charts that compare the Phoenician, Greek, Gothic and runic alphabets.

Yet nowhere in his thousands of pages did Rudbeck explain what he saw in the lines.

My interest deepened when I learned that the diagram related to an actual stone – the very stone Renhorn described half a century later.

In fact, that stone was located in the region where Rudbeck had sent an expedition scouting material for his Atlantica. In 1675, three of his students explored the mountains up near the Norwegian border in Jämtland, Dalarna, and Härjedalen – regions that had in parts become Swedish only three decades earlier.

The Beard of Atlas

From a 17th-century panorama begins a journey into the Swedish mountains and the myths behind them – resurfacing in the 21st-century reality of the forests up north.

Otto’s Original

From Sweden’s north, the expedition had returned with a rich harvest that included drawings of mountain panoramas, maps, and measurements.

At Uppsala, their observations provided Rudbeck with new evidence in his quest to link ancient myth to the landscapes of his homeland. Though the stone remained ‘mute’ in the Atlantica, the protagonists of its first emergence now came into view.

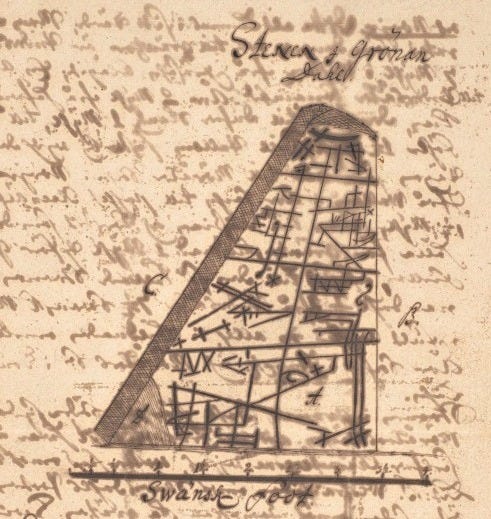

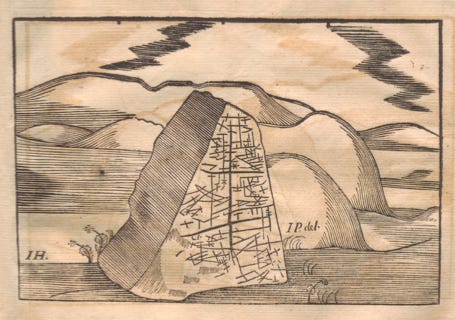

Among the students Rudbeck sent north in 1675 was Samuel Otto. Three years earlier, Otto enrolled as a student of engineering at Uppsala. For the Atlantica, he acted as one of Rudbeck’s draftsmen, contributing a number of woodcuts to the work. The enigmatic diagram of the stone was one of them, so I learned.

A sketch survives in the National Library in Stockholm of the printed illustration; a folded piece of paper considered an original by Samuel Otto.4 On the basis of this document, scholars assumed that Rudbeck’s 1675 expedition had visited the stone Renhorn later described in his dissertation; a stone located some kilometres north of Storlien in western Jämtland.

Within sight of the Norwegian border, Rudbeck’s student had allegedly produced the paper drawing of the stone. Later, this sketch served as model for the woodblock eventually printed in the Atlantica.

Peringskjöld’s Papers (1700s)

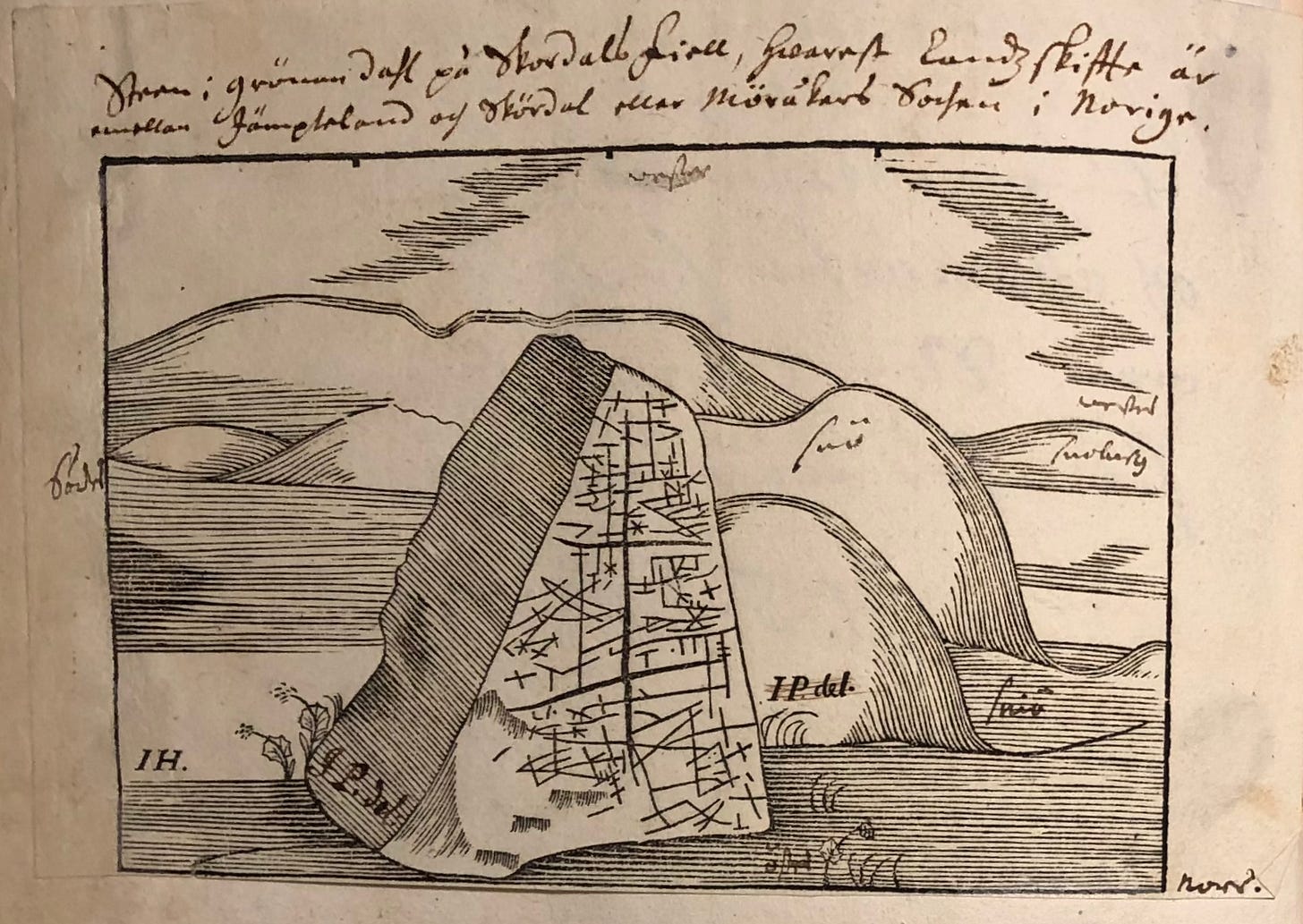

Today, the handwritten drawing attributed to Otto is preserved at Stockholm among the papers collected by Johan Peringskjöld. Until his death in 1720, this Swedish antiquarian had worked on a comprehensive catalogue on Swedish rune stones.

Peringskjöld counts among the few scholars who in the 17th century had personally seen the stone near the Norwegian border. He had done so as part of another expedition that had as well been initiated by Rudbeck – this time as a side quest of a mission whose purpose was to lead him beyond the Arctic Circle in 1687, to another stone reportedly inscribed with an unknown alphabet.5

Based on an illustration produced by Peringskjöld and his travel companion Hadorph, a woodblock of the stone was prepared. There seems to be a test print drawn from it surviving among Peringskjöld’s papers. In these, he apparently collected material for the Jämtland-section of his work on the rune stones of Sweden (it is the same section in which also the mentioned drawing attributed to Samuel Otto survives).

The woodcut shows the initials (‘IP’ and ‘IH’) of Johan Peringsjöld and Johan Hadorph, the two antiquarians visiting the site in Jämtland in 1687. On the same page, handwritten modifications were added to the print, potentially for a coming iteration of the woodblock (including, for example, a caption, cardinal points, and instructions to an artists to elaborate landscape features such as ‘snow’, ‘lake’). This iteration, so it seems, was never carried out.

After Peringskjöld’s death in 1720, when Renhorn embarked on his dissertation on the stone, he managed to gain access to the original (non-revised) woodblock. It was this version he used it to illustrate his work on the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ printed in 1733 – the foldout that had stood at the beginning of my paper trail.

Part III: Roots of a Legend

The trail leads south to Denmark and back in time, when antiquarians sought anchors for a prophecy of cultural decline circulating during the Reformation. Reshaped by political and religious agendas in Sweden, this prophecy eventually migrated north.

Worm’s Wormhole (1643)

Access to this rare visual material from Sweden’s North was not the only ace Renhorn pulled from his sleeve. As he writes in his dissertation, the Royal Secretary Johan Helin still remembered opinions which the late Peringskjöld had formed on the stone, but had never come to comment: Rather than a prophetic object, Renhorn relates, Peringskjöld saw in it a border stone between Norway and Jämtland, its six main fields representing the six assessors of the border judge.6

In Peringskjöld’s interpretation, the old legend of a prophetic ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ was superseded by a far more prosaic reading. A more reverent comment on its mysterious lines appears in an 18th-century annotation beneath the woodcut:

May their meaning be known to the highest God and those who applied themselves to it.7

When Renhorn defended his dissertation in 1733, the legend attributed to a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ seemed already faint. A century earlier, the search to connect its prophecy with a tangible object was in full swing.

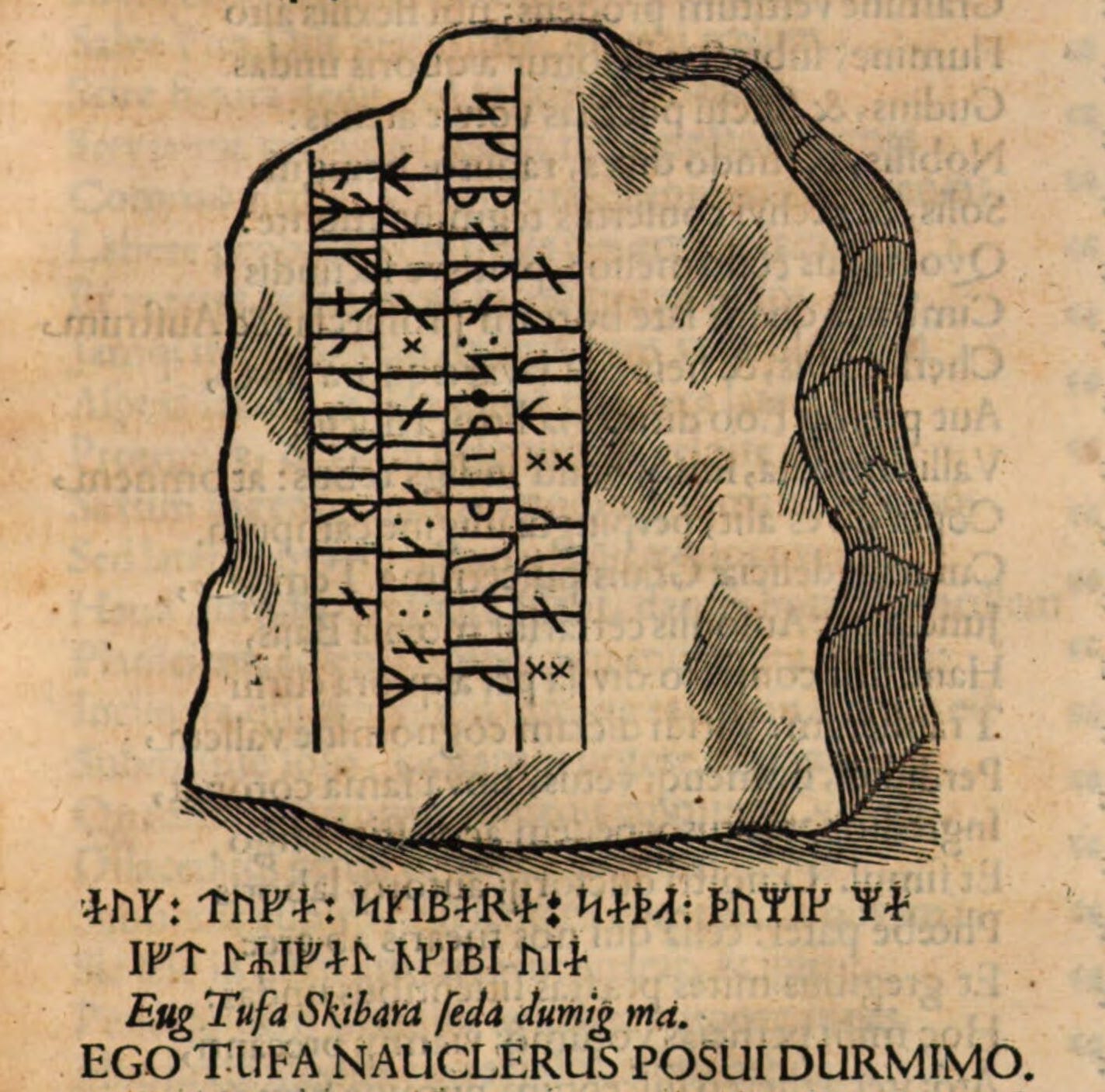

In 1643, the Danish antiquarian Ole Worm published the massive Monumenta Danica on the rune stones of his homeland. At great length, Worm explored traditions that spoke of a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ inscribed with fateful words.8

It was in Denmark that Worm mentions a saxum Grøndallense (‘Stone in the Green Valley’), printing an illustration thereof as part of his work. According to documents he mentions, that stone was inscribed with a prophecy foretelling violent upheavals that occurred in Jutland during the Reformation.

Echoes of this tradition, Worm relates, he found in a manuscript from 1503. It told of a cleric coming across a stone with brass letters in a forested valley called Grøndal (‘Green Valley’), denouncing decaying morals and predicting social upheaval at a time when churches were becoming prisons and priests peasants.

The same tradition also found its way into the Eclogues (1560) written by Michael Laetus, a Neo-Latin poet writing during Denmark’s Lutheran turn. In one of these pieces, a poet arrives in an idyllic ‘Green Valley’, and from the weathered lines of a stone deciphers a dire prophecy of a similar fate.9

Across various genres, the prophecy about the end of the known world resonated in Denmark with amid the upheavals of the Reformation.

The Compass Shifts North (1612)

As antiquarian, Worm was looking for was the actual stone in which this tradition rooted. This was where problems began.

The prophecy and the rune stone at hand, Worm concedes, didn’t match. The four worn-out lines of runes he printed as part of his Monumenta (see above) had nothing to do with that story of social upheaval and the known world collapsing.

And so, Worm began considering that the stone and its legendary ‘Green Valley’ could be located elsewhere.

His scouting led Worm to Johannes Messenius. In his Specula Sueciae (‘Mirror of Sweden’) from 1612, this Swedish historian mentioned a stone inscribed with runic script and a familiar-sounding prophecy that foretold the end of the world, monasteries crumbling, priests becoming peasants, and the foreboding stone lying fallen on the ground.

This stone, Messenius wrote, was located near the Norwegian Alps in Jämtland (then part of the Danish Crown). There it had supposedly been placed during the reign of Erik Stenkil (c. 1060).10

Worm followed this trace further back, to Laurentius Petri (1499–1573), the archbishop of Uppsala. His bishopric included Jämtland in today’s Sweden.

Petri was another person said to have personally visited the stone. At least, the priest Jesper Marci claimed to have found this information in the bishop’s library after his death, together with a description of the stone and the prophecy.

Using the lore of a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ in Jämtland and its warning prophecy, the Lutheran preacher composed a song that exhorted pagans and papists to reform. To the present day, Worm notes, the Swedes sang this song with deep admiration.

Part IV: Anchoring the Myth

Topography, myth, and state-sponsored visual culture converge as Swedish antiquarians and artists give the stone in Jämtland a tangible anchor. Figures like Erik Dahlberg illustrate how landscape and prophecy were creatively merged as part of national-historical narratives, while Daniel Tilas stands for the disenchanting glance at nature of later decades.

Reaching for the Green Valley

On a stone there is a poem

that is written in runic script.

The poem was not put there yesterday.

Between Norway and Jämteland,

it has been read by many women and men.

It has stood for many years.

It has now fallen over,

because of us …Song of the Stone of the Green Valley (stanza 7)

The prophetic tradition, now popularised in a Swedish song, had wandered through various media and ideological landscapes across centuries. Catholics and Lutherans alike refashioned it according to their own agendas.11

Messenius had already noted the prophecy’s pragmatic use – and concluded that the entire tradition was likely invented to begin with. All this, he caustically concluded, seemed more likely than that a real stone would ever turn up in Jämtland.12

Ole Worm, however, had not given up.

The Danish antiquarian left nothing unattempted to investigate the Jämtland trace, he asserts in his Monumenta. In following the lines of the song up north, he was not alone.

Already in 1601, the father of Swedish runology Johannes Bureus (1568–1652 ) had written to the governor of Jämtland about the ‘rune stone in the Green Valley’ up north – yet to no avail.13 Worm sent letters to the then-archbishop in Uppsala who was in charge of Jämtland. They brought him a little closer – yet again, not close enough:

They say that there is a valley of that name in that region, and there are also rumours of a stone – but no one has yet been found to show what remains of it.

Ole Worm, Monumenta Danica, p. 311

The Northern Face of the Prophecy

Half a century later, things started to move again.

In the 1670s, when Olof Rudbeck was working on his Atlantica, the Swedish polymath sent out an expedition to the region that had defied the inquiries of Worm and Buraeus (see Part II). His Atlantica became the first book to print the illustration of a stone still found today near the Norwegian border, leaving it uncommented.14

Interest revived around the same time as the Swedish Board of Antiquities began compiling lists of ancient monuments. From all across the kingdom, they requested reports on antiquities that were capable of shedding light on Sweden’s past.

In 1685, the local judge Plantin followed up on such requests. Nobody he consulted in western Jämtland, Plantin related to the south, had heard anything about a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’.

What the men from Undersåker parish did report though was a stone near Skurdalsporten into Norway, inscribed with runes on its northern side.15

It was this object Peringskjöld came to see and draw two years later (see Part II). Yet it was only in the early 18th century that this stone was explicitly linked to the prophecy connected to a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’.

Christening the Stone

The work to institute this union was the most monumental one to appear in Sweden at the time.

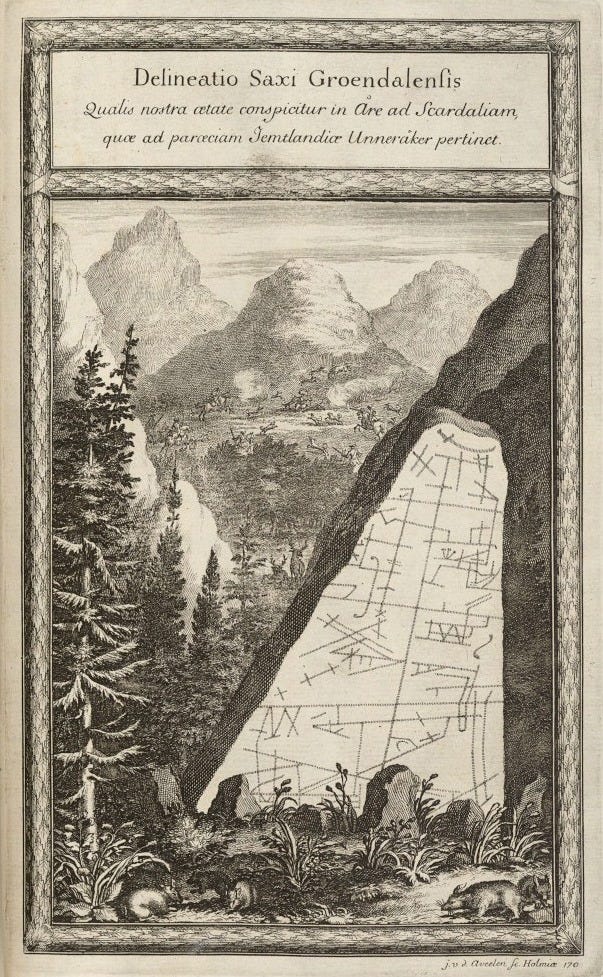

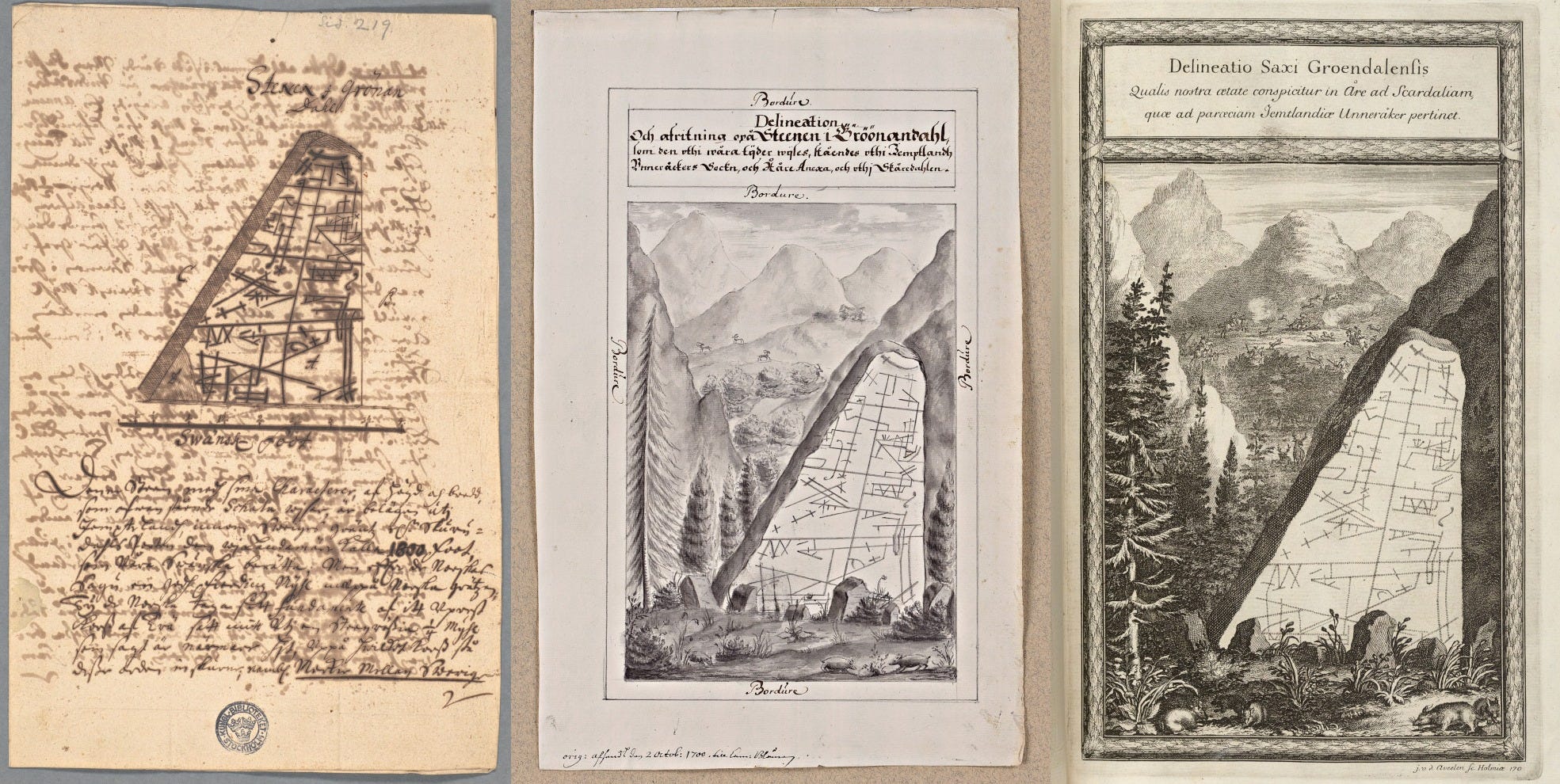

When Olof Rudbeck was producing the volumes of his Atlantica, the artist Erik Dahlberg engaged in a project of even greater visual ambition. In his Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna (‘Ancient and Modern Sweden’), Dahlberg set out to depict cities, palaces, and antiquities from across the kingdom in lavish copperplate engravings.

For this, Dahlberg enjoyed enormous funding from the Swedish crown. The Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna was meant to visually represent the entire kingdom in unmatched grandeur. However, from the northern provinces of the kingdom (and that of Jämtland in particular), Dahlberg had little to represent.

Around 1700, the artist therefore seized on the rumours of a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ up north to fill this gap. It was his Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna that gave the prophesied stone a face.

Among the 353 engravings of this work, a stone similar to the one in the Atlantica appears, here embedded in a mountainous landscape. The title locates the stone near Skurdal, in the parish of Undersåker. Here the name ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ first was used for that stone in print.

Dahlberg’s Design

Like Rudbeck, Dahlberg had never travelled to Jämtland himself.

Instead, he had gone through the governor of Jämtland. With a letter sent in 1700, Matthias Busch – land surveyor in Norrland – had forwarded a sketch of a stone he found near the Norwegian border, labelled the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’.

However, none of the persons he consulted, Busch warned, connected the stone to the prophetic song (they considered it a border stone instead). Furthermore, the natural surrounding did not seem to fit the story of ‘the’ stone at all.

If this was truly the ‘Green Valley’ of the song, the surveyor wrote, then either nature had changed dramatically over a few centuries – or the songwriters had never seen the place they described.16

Dahlberg, however, decided to override the land surveyor’s concerns.

He forwarded the sketch to Stockholm. On this basis, Johannes Litheim – one of the artists Dahlberg employed – proposed a first sketch for the Suecia’s engravings. In this, Litheim invented a ‘Green Valley’ and placed Busch’s drawing of the stone within it, embellishing the dramatic mountain landscape with alpine theatrics such as spruces, bear hunters, reindeer, and lemmings.17

Above this scene, the name ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ was placed, as given in the ancient prophecy. This way, the ‘Green Valley’ visually materialised – not from observation, but from artistic invention.

Disenchantment

The Suecia’s launched the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ in Jämtland into public view as a visually powerful image, though stripped of the complex tradition behind it. The explanatory texts Dahlberg envisioned to accompany them never made it into print. The engravings of the stone thus appeared without any discussion of the stone, leaving the meaning of its lines as elusive as ever.

In the decades after the Suecia’s publication, real-life encounters with the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ meant a sobering reality check for travellers to Jämtland.

Border inspector Nils Marelius noted nothing green at all about that fjäll-region when he passed the stone around 1750: He and his men hardly found enough fodder for two of their three horses.18

And then, there was the problem with the lines themselves.

Busch had already cast doubt on the idea that the stone’s lines represented letters of any kind. In fact, as he related in his letter, many stones around Skurdalsporten exhibit similar patterns.

Coming visitors concurred.

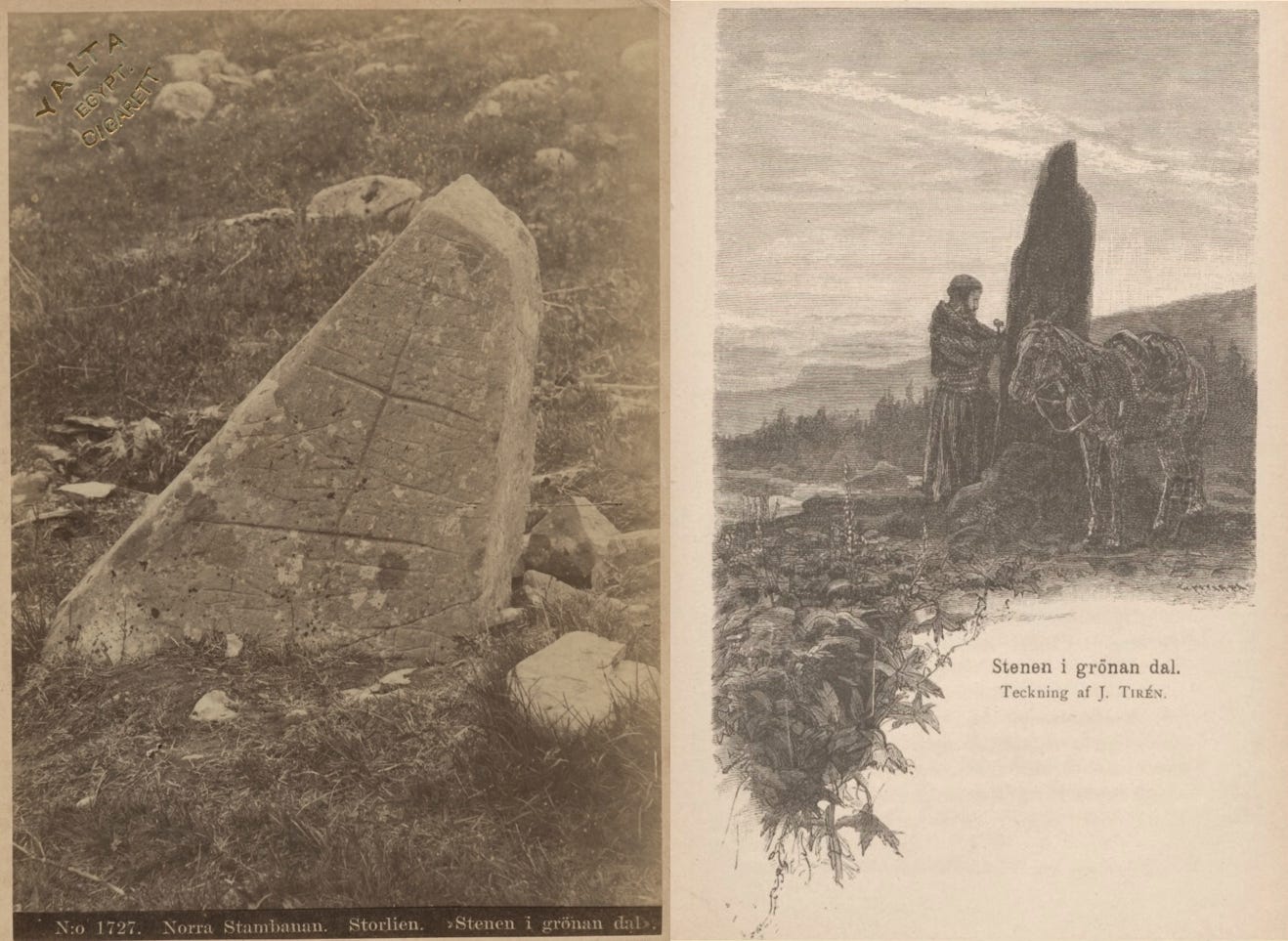

In 1742, Daniel Tilas arrived to the site. In a geological handbook this Swedish mineralogist published two decades later, he dedicated several pages to the stone.

Tilas found the stone lying flat and – tongue-in-cheek – propped it back up again, as if to stall the old prophecy from fulfilling itself.

By the time he visited, Tilas relates, Dahlberg’s identification of this stone near the border had caught on with local farmers. He mentions the pride with which the men now told him that this was the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ known from the famous song (and that its original inscription had effaced in the meantime).

In his own assessment, Tilas painted a more sobering picture.

He told that both Rudbeck and Dahlberg had exaggerated the regularity of the lines when printing the stone. For him, there was nothing special about them at all. He was convinced they were nothing more than cracks – natural formations, a simple game of nature.

All around him, Tilas points out, there were stones of this kind:

“This region has enough ‘Stones in the Green Valley’ for all the world to claim one,” the mineralogist concluded.19

Part V: Tourism and Restoration

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the stone becomes popularised through tourism and publications. Through restoration, photography, and the involvement of national institutions, layers of meaning are evaluated, effaced, and inscribed into today’s appearance of the stone.

And Along Came Tourists

Since Dahlberg’s Suecia antiqua et hodierna, the name ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ stuck with the Jämtland stone. 18th-century antiquarians continued to administer legend and history, collecting and interpreting the ever-growing body of material about the stone.20

When Johan Törnsten and Pehr Abraham Örnskjöld published their map of Jämtland-Härjedalen in 1771, a ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ appeared next to the Norwegian border. For decades, it flickered in and out of maps of the region.21

Similarly, the stone’s mysterious aura continued to persist against more rational voices.

In 1882, the railway connecting Östersund and Trondheim was completed. At Storlien, the last town before the Norwegian border, a kind of Swedish Zauberberg began attracting ‘clean-air guests’ (luftgäster) from the south. Both the Swedish Tourist Association (STF) and the Skiing Association (Skidfrämjandet) turned the site into a new centre for year-round mountain tourism.22

The efforts of these institutions also shifted the stone to the centre of new attention.

In reports published in the STF-journal, visitors to Storlien mentioned it as an attraction in the nearby fjäll; an object layered with historic meaning which was allegedly first inscribed by Saint Staffan himself.23

The cultural imprint the stone left during this period can be traced through newspapers publishing updates on the local sight, artists who imagined scenes from its alleged history for guide books on the now-accessible region, and even cigarette brands, which featured the stone in collectible card series.24

Flanking these popularising strands, scholars offered public lectures and published discussions of the stone. In these, they tried to disentangle an expanding net of lore from a stone that, as one author concluded, across centuries had become “a coat hanger for the Swedish version of the prophecy of the Stone in the Green Valley”.25

Fixing the Prophecy

The growing number of visitors, however, literally left their mark on the stone.

Already in 1742, when Daniel Tilas inspected the stone, he noted that its sides were covered with the marks of those attracted by its newfound fame. To these, Tilas added his own coat of arms, as he proudly relates in his report.

This habit continued for centuries.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the numbers of those who escaped the ‘dust and stench of gasoline’ for the ‘clean, light, almost intoxicating air’ at Storlien rose considerably.26

In 1933, Skidfrämjandet and the National Railway began expanding the hotel facilities.27 As tourist capacities increased, the danger grew for the precious attraction near the border. It was at this time when Skidfrämjandet launched an initiative to restore the carving-damaged attraction on its territory.

By 1933, concerns about preservation prompted Skidfrämjandet to contact the National Board of Antiquities (RAA). Plans for a restoration in the following summer took shape.

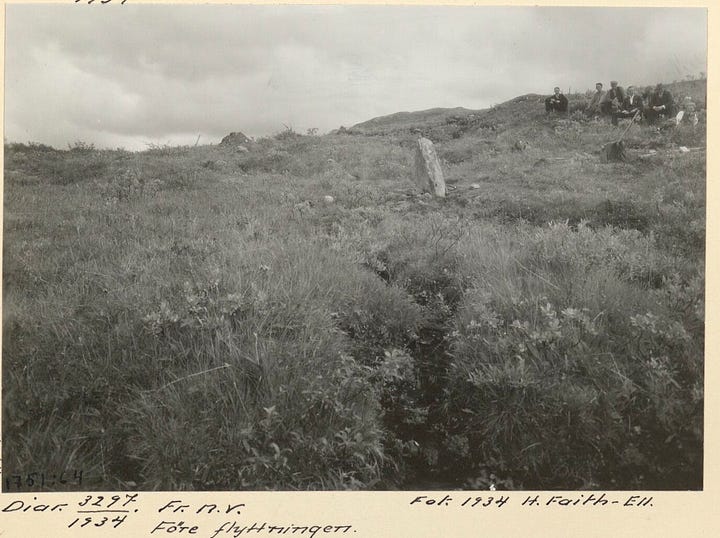

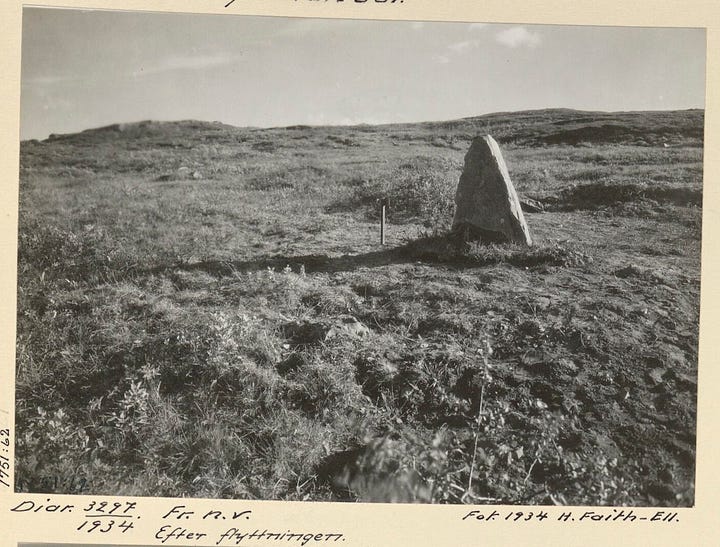

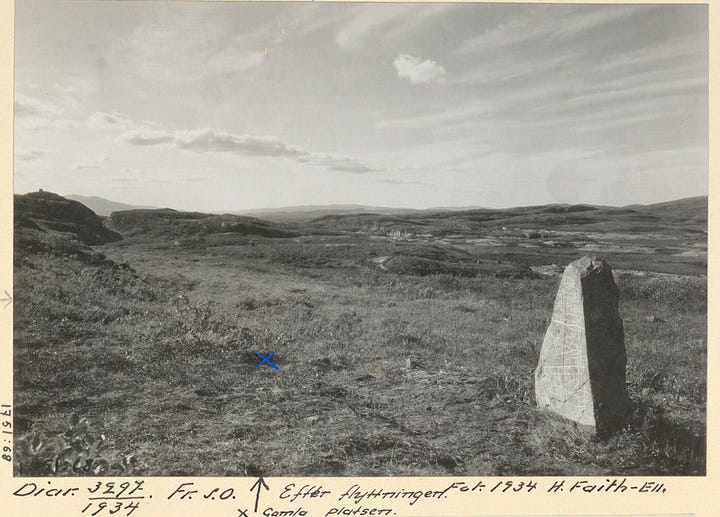

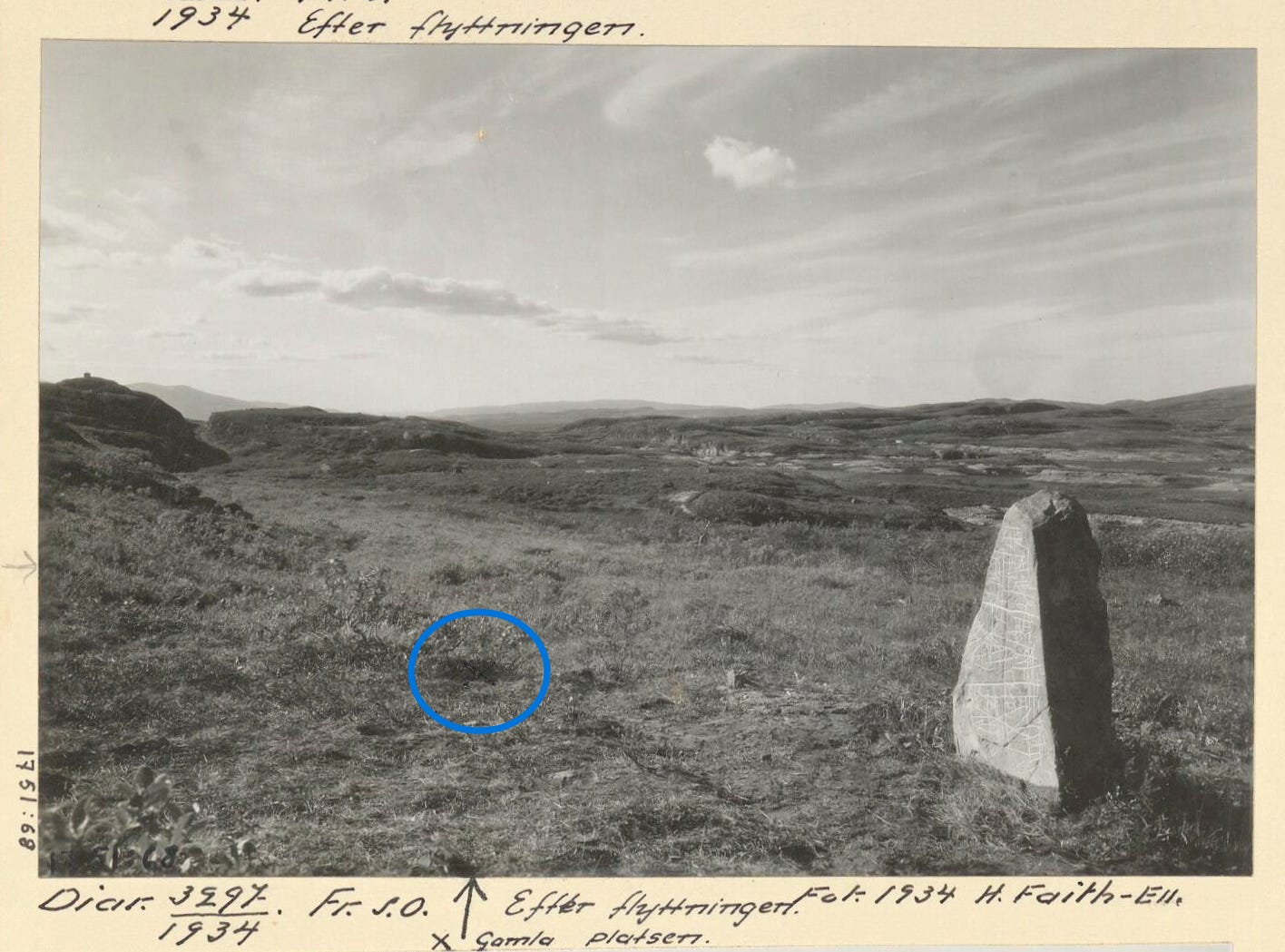

On 31 July 1934, RAA Director Karl Alfred Gustawsson met with Railway Board Secretary Carl Nordensson and regional antiquarian Eric Festin at the site.28

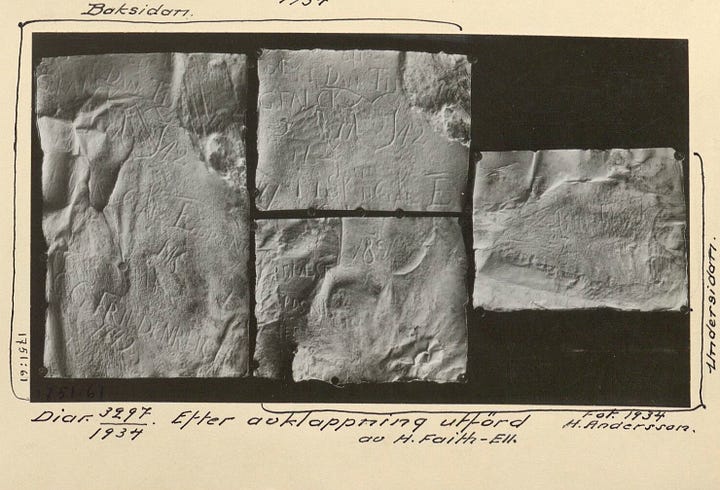

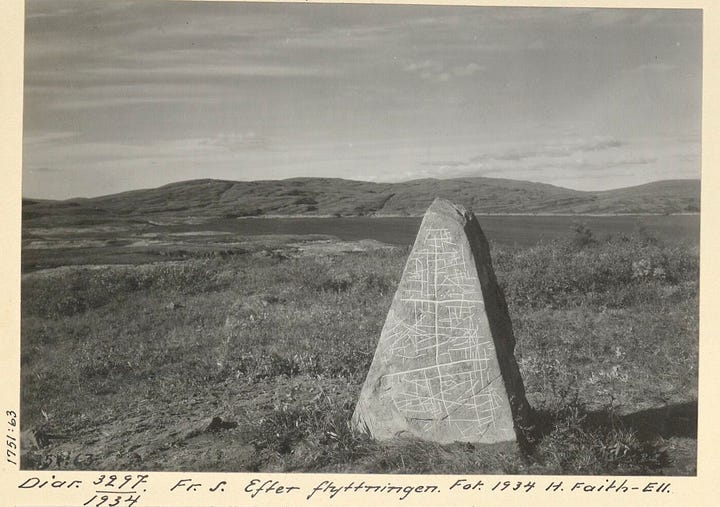

Photographs Gustawsson took on this scouting trip show the object in question covered with lichen and provisionally propped up with rocks, describing the lines on its face as “ristningar” (‘carvings’ – his quotation marks), though he suspected they were natural formations (“naturbildningar”) later touched up by human hands later with rune-like marks.

During the visit, the men discussed and defined steps of conservation. The RAA director explains that he personally marked a hole where the stone should be placed, a little eastwards on drier ground.

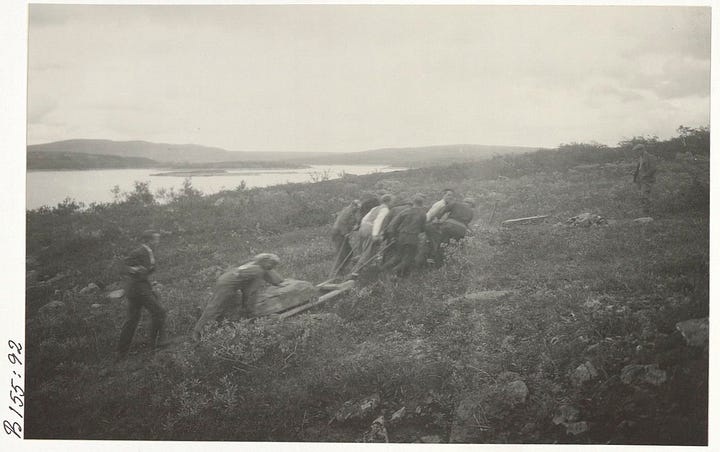

In late August, an RAA conservator and a photographer arrived to Storlien. On site, they supervised and documented the restoration works as instructed after the director’s visit.

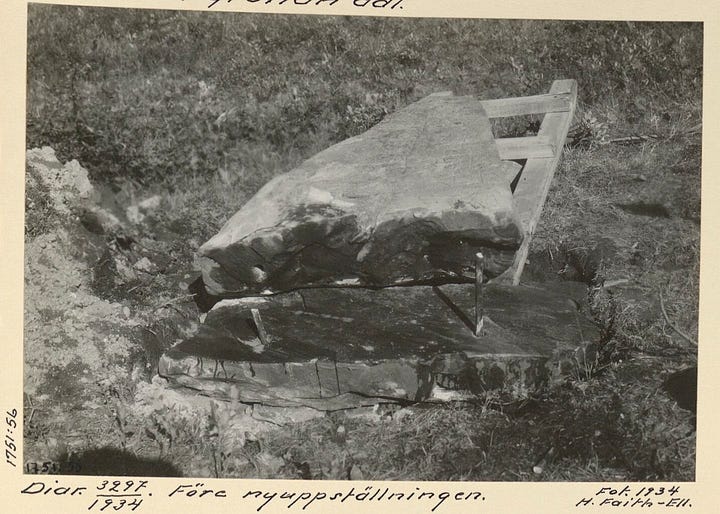

The stone was moved ca. 20 meters eastwards, cleaned, and photographed, while moulds of its surface were created.29 Holes and recent carvings in the stone were mended.

Then, it was raised again and secured with two iron rods onto a rock plate, which rested on a bed of concrete and crushed stone filled into the ground. The stone was repositioned, and an RAA plaque ultimately installed nearby, pointing out the stone’s status as an ancient monument protected by law.30

Politics of Preservation

As the sun set over the ‘Green Valley’ in late August 1934, lines whose meaning had eluded generations brightly shimmered through the twilight. As part of the restorations, white paint had been applied to the stone’s front side.31

The representatives of a government institution had given the stone a new face and position in the ‘Green Valley’. As they had done with rune stones further south,32 RAA used paint to highlight the lines and applied concrete and iron bars to fix an object whose symbolic power rested on its capacity to tip over.

The 1934 restoration created a new layer in the stone’s ever changing history. At a time when popular culture and expanding tourism had physically left their mark on it, RAA officials decided which parts of its history to highlight and which ones to efface.

The RAA plaque placed next to the stone officially elevated the status of the humble stone to a monument of national interest. At the same time, this measure further cemented its status as a tourist attraction (this ambivalence echoes in the fact that the operation was initiated by and carried out through members and the networks of Skidfrämjandet, and was fully paid for by the manager of the Storlien hotel).33

Painting the stone’s face and fixing it in the landscape, the restorations materialised one interpretation of the stone. Not all were happy about this outcome.

From early on, regional antiquarian Eric Festin had deplored the vandalism of the stone and proposed it to be restored.34 In 1933, RAA director Gustawsson eventually involved Festin in the planning phase of restoration works. Festin proposed measures according to best practice, and was on site near Storlien in summer 1934, when Gustawsson came north to discuss them on site.

Although Festin seemed integrated in the process, his later words on the restorations read bitter. In an article published the subsequent year, he complained that the works were carried out poorly.

Moreover, the stone had been moved to a different place – further away from the border (Festin had strong opinions about the stone’s original position as well as its function).35 At their meeting at the stone in July 1934, he deplored, it had been agreed that the stone would not be moved from its then position.

The RAA Director-General overrode this agreement with the stroke of his spade.

Part VI: The Circle Closes

The narrative comes full circle, reflecting on the stone’s layered history as a palimpsest of meaning. Ultimately, the stone stands not as a vessel of prophecy, but as a symbol of humanity’s enduring quest to read meaning into the material world.

By 1934, the elusive object of prophecy stood as a stabilised object – anchored by concrete, paint, and institutional authority.

Today, the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ still stands at the site Gustawsson marked on the ground. Its current position and form are just one layer among many, each invisibly inscribed into the stone’s long and shifting history – overlapping, contradicting, effacing each other in ways that from our vantage point may ultimately remain elusive.

Perhaps, it is from this quality that the lure of the stone ultimately springs.

Rather than bearing a single meaning, the stone stands as a tangible symbol of the ongoing, layered process by which humans connect dots and trace lines in their quest for resonance with the world around them – either individually or through institutions they build to hold meaning.

From the antiquarians’ centuries-long search for a physical anchor to the prophecy may speak a deeper hope; one we still share today: that even in times of upheaval, a message may still be inscribed in the world, a form of resonance or even guidance to be discovered and deciphered in that palimpsestic process by which our mind inscribes it with meaning.

This process goes in cycles and ultimately may never be complete, as a final episode from the history of the stone suggests.

At the time when Axel Nelson (working as librarian at the National Library at the time) edited the Swedish text of the Atlantica published in 1943, he also touched on Rudbeck’s unexplained diagram of the stone. In his notes to the text, Nelson disputed the idea that Rudbeck’s student Samuel Otto (see Part II) had drawn the paper sketch preserved in Stockholm from the actual stone in Jämtland.36

Instead, he argued, Otto had drawn the stone from this sketch.

Encountering a stone at the border, Nelson’s speculated that Otto had first sketched the lines of a naturally creased stone on a piece of paper. Then, he could have embellished these lines with patterns reminiscent of Sámi drums – ritual objects that Otto – himself from Norrland – had helped Rudbeck acquire.37

Otto may have carved his invented design into an actual stone, thus creating a hybrid artefact at the Jämtland border. After the return of the 1675 expedition, he left the paper sketch with Rudbeck.

Though he had it printed in the Atlantica’s volume of plates, Rudbeck never came to unfold the ideas which this fabrication was supposed to buttress.38

It would not have been the first case in which Rudbeck had evidence created to tell a story according to his agenda.39 Whatever master narrative Rudbeck had in mind – whether and how he related it to the prophecy of the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ – remains a mystery.

What remains are furrows on a stone, shaped by time and touched by centuries of human intervention, the paper trails that lead into its history, and the lines we continue to draw between them from our wish to find meaning.

Further Reading and References

All translations and photographs are my own unless stated otherwise.

Acknowledgments

For their support of my research for this article I would like to thank the staff of National Libary Stockholm, RAA Stockholm, and Järnvägsmuseum Gävle.

The Visby Stone

In Sweden, too, people continued to link the prophecy of the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ to further local objects and contemporary events.

In Visby (Gotland), there is a sitting slab is preserved in a niche in the town wall. It is marked with years linked to events from the reign of Gustav III. Underneath, an inscription quotes the song’s line ‘Alltid står stenen i grönan dal’ – (‘Always stands the Stone in the Green Valley‘) – lines that may have resonated with wish for political stability associated with the regent’s period.

Please note the general bibliography available here.

This will be a separate story to be published on my forthcoming writing platform “Into Awe”.

Johan Hermansson (praes.) / Johan Renhorn (resp.), Specimen academicum de lapide in valle virenti, vulgo Stenen i grönan dal …, Uppsala 1733 (online at diva-portal.org).

You can explore these illustrations on our visual database Reaching for Atlantis.

The trace between the illustration and the 1675 expedition leads via Petrus Törnwall. Törnwall was the other draftsman on whom Rudbeck had relied in preparing the woodcuts for his Atlantica. In a handwritten register kept at Uppsala, Törnwall points out that the drawings underlying the stone (fig. 96), as well as the mountain panoramas from the 1675 expedition, were prepared by Samuel Otto. See Axel Nelson, “Samuel Otto och Olaus Rudbecks Atlantica. Ett bidrag till Lapplandsforskningens äldre historia”, Kungl. Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala 1943, 56–88.

For a first introduction see Henrik Schück, “Torneåstenen”, in: Fornvännen 28 (1933), 257–68 (online at raa.se).

Renhorn (resp.), De lapide in valle virenti, pp. 22f. The idea that the ‘so-called stone in the Green Valley’ marked the border, which was (re)drawn between Skurdal and Jämtland after the Peace of Brömesbro (1645), is also given in Fabian Törner (pr.) / Johan Sparrmann Eriksson (resp.), Dissertatio gradualis de fatis Jemtiae …, Stockholm 1722, p. 23.

Stockholm, National Library, Ms. F h 5. Transcription of the caption (as given in Harald Wieselgren “Stenen i Grön dal”, in: I gamla dagar och i våra. Småskrifter, Stockholm 1900, 113–23, p. 117): “Thenne stenen som han här står afmålat ähr funnen långt upp i fjällen mellan Norge och Jemtland, dock inom Sveriges gränser, uti en sokn som heter Undersåker, vid pass sex mil derifrån: är funnen af några böndr der i landsorten och låg neder på marken, hvilken sedan af pastoren der sammastädes blef upprest. Uttydningen på dess Caractèrer må den högste Gudh vara bekänd och dem, som sig deruppå lagt hafva.”

See Ole Worm, Danicorum Monumentorum Libri Sex, Copenhagen 1643, lib. V, pp. 304–311.

On Laetus and his eclogue Myrmix see, with further references, Marianne Pade, “Enmeshed Identities – The Stone in the Green Valley’, in: The Poetics of Things Past. Gedichtete Geschichtsdinge. Transmission of Knowledge in Verse from Antiquity to Early Modern Times, eds. Maren Elisabeth Schwab, Stefan Feddern, Jochen Schultheiß. Andreas Schwab, Baden-Baden 2024, 323–37, pp. 323f.

Cf. Messenius, Specula Sueciae, Stockholm 1612, p. 58 (digitised on Google Books).

The Danish antiquarian Anders Sørensen Vedel also mentioned a stone located six miles from Viborg, inscribed with a similar prophecy about the overturning of known social order. See Marita Akhøj Nielsen, Anders Sørensen Vedels filologiske arbejder 1–2, Copenhagen 2004, p. 486. Hans Christensen Sthen wrote a school drama on the prophecy; see Wolfdietrich von Kloeden, Art. “Hans Christensen Sthen”, in: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon, vol. 14, Herzberg 1998, coll. 1532–1534.

The line of argumentation went like this: To serve in their efforts against the Lutherans, the papists had antedated the prophecy to the time of Staffan the Saint. Jesper Marci later had simply changed its vector. Rewriting it as a Swedish song, he had repurposed the prophecy as ammunition against the papists in the Liturgical Struggle under King John III.

These thoughts of Messenius, however, did not appear before the 1700s. See, with further references, Wieselgren, I gamla dagar, pp. 115f.

See the journal notes of Buraeus, edited in G. E. Klemming, Ur en samlares anteckningar, Stockholm 1887, pp. 8–14.

While Rudbeck’s pages remain silent about its lines, we may still conjecture that he was familiar with the prophecy of the ‘Stone in the Green Valley’ – if not through the famous song itself, then through Ole Worm, to whose Monumenta he refers across the Atlantica.

See Wieselgren, I gamla dagar, p. 116.

The letter from 18 August 1700 includes a long description. It is kept at Stockholm, National Library, HS M 11:8:2 (online at suecia.kb.se). For a partial transcription see Wieselgren, I gamla dagar, p. 119.

The correspondence is retraced in Nelson, “Samuel Otto”, pp. 81f.

For the ‘real’ stone mentioned in the song, Marelius continues, one should rather look elsewhere, perhaps in a region called ‘Gröndalen’ in Härjedalen. See Nils Marelius, “Anmärkningar rörande Herjedalens och Jaemtlands Gränts emot Norrige, gjorde vid Gränse-mätnigen, åren 1758, 1759 och 1760, samt ingifne”, Kungl. Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar 1763, 289–312 (online at KVAH), p. 301. Cf. Johan Lindström “Saxon”, I Jämtebygd. Studier och skildringar, Stockholm 1888, pp. 78f.

See Daniel Tilas, Utkast til Sveriges mineral-historia, Stockholm 1765, pp. 66f. (online at alvin-portal.org).

Among them are the collections by Schering Rosenhahne (Stockholm, RAA, Rosenhaneplansch Norrl II 13 14 14a) or Elias Palmskiöld (Uppsala, University Library, Palmskjöld no. 308). The latter was involved as antiquarian in Dahlberg’s monumental work and brought together contemporary and mediaeval sources in a collection still surviving at Uppsala. As guide through the material see Lennart Björquist, “Elias Palmskiölds anteckningar om stenen i grönan dal”, Svenska 1939, 54–60. For an introduction to Palmskjöld’s collection at Uppsala see Severin Bergh, “Elias Palmskiöld och hans samlingar”, Nordisk tidskrift för bok- och bibliotheksväsen 1915, 81–145 (online at runeberg.org).

See the 1771 Örnskjöld-Törnsten map, digitised by Stockholm, National Library.

Cf. Carl Nordenson , “‘Nya Högfjället’ i Storlien”, På Skidor 1935, 361–9, p. 362.

See ‘Aquila’, “Storlien. Några reseminnen”, Svenska Turistföreningens Årsskrift 40 (1890), 29–40, pp. 35f (online on runeberg.org).

For example, the local teacher Backlund passed Skurdalsporten on his way back from Norway on 5 June 1895. He reported to have found the stone tipped over and sunken into moss, and raised it up again (Östersundsposten, 1 August 1895). In 1934, the restoration of the stone documented inscriptions found at its bottom. This suggests that the stone had lain tipped over for longer periods.

At Stockholm, the Yalta cigarette brand printed the stone as part of its collector cards. It was included among motifs from the Northern Main Line (Norra Stambanan), the newly opened railway line that created access to this part of Sweden (other motifs included Åre and Tännforsen).

The artist Johan Tirén created historicising illustrations depicting the stone’s legendary history, see Lindström “Saxon”, I Jämtebygd, p. [78B] (depicted in the article above).

Wieselgren, I gamla dagar, p. 123. See also Nils Ahnlund, “Helge broder Staffan”, in: Oljoberget och Ladugårdsgärde. Svensk sägen och hävd, Stockholm 1924, 153–79.

Cf. Elin Hedberg, “Sommardagar i Storlien”, På Skidor 1934, 297–300, p. 300.

The project is described by Nordenson, “‘Nya Högfjället’ i Storlien”.

My account builds on the 1934 correspondence preserved at RAA. On Festin see J. E. Modén, “Eric Emanuel Festin”, Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (online at sok.riksarkivet.se).

Documentation states that a total of nine moulds from the stone was once preserved at RAA. However, a recent search for them did not yield any results (correspondence with Annelie von Wowern of RAA, 02 June 2025).

The bottom region then was covered with grass. Repositioning the stone, its carved face was oriented as previously (32° west of north), and its vertical axis of symmetry aligned with the plumb line. I draw on the instructions by Gustawsson preserved at Stockholm, RAA, 13.08.1934 (D.nr. 3040) and the report by conservator Giris Olson, 05.09.1934 (D.nr. 3297).

This detail is not mentioned in Gustawsson’s instructions, but can clearly be seen on the photographs after the 1934 restoration. The caption of one of the 1934 photographs (Diar. 3297.1934, 1751:51) refers to “Uppmåln.[ingar] av Faith-Ell”. On photographs taken three years later, these highlights seem to have vanished again (cf. Photographer G. Ewald, Stockholm, RAA, Acc. nr. 82-730-1).

See Karl Alfred Gustawsson, “Restaurering av runstenar”, Fornvännen 1941 (36), 243–5 (online at diva-portal.org).

The key actors all ranked among the 25.000 members of Skidfrämjandet. Cf. the note “Stenen i grönan dal” in the association’s journal Svensk Skidkalender (1935), pp. 176f.

In their letters, Gustawsson, Festin, and Nordensson corresponded with each using a ‘du’ basis, addressing each other as ‘Broder’ (‘brother’). Nordensson (Secretary of the Railway Board) had organised the train tickets. Skidfrämjandet, who ran the nearby hotel, provided stays on site. Its manager – the Stockholm businessman and sports functionary Teodor Bång – had agreed to personally carry all costs of the operation.

On Bång see Vem är vem i Norden. Biografisk handbok, ed. Gunnar Sjöström, Stockholm 1941, p. 1013 (online at runeberg.org).

Already in December 1927, Festin had proposed a restoration of the stone to Skidfrämjandet when it became the owner of the early resort at Storlien. See Eric Festin, “Stenen i grönan dal. Några erinringar”, På skidor 1935, 167–180, p. 168. See also Eric Festin, “Om ‘Stenen i grönan dal’. Några erinringar och en gensaga’, Fornvårdaren 5 (1933), 183–91.

See Festin, “Stenen in grönan dal” (1935).

Axel Nelson, “Efterskrift”, in: Taflor till Olaus Rudbecks Atlantica, ed. Axel Nelson, Uppsala-Stockholm 1938, 6-9.

The scholar Ernst Manker later argued against any local (southern Sámi) traditions influencing the actual pattern on the stone; see Ernst Manker, “‘Stenen i grönan dal’ och lapptrummorna”, Rig 28 (1945), 25–33, esp. pp. 30–33.

See Nelson, “Samuel Otto”, pp. 80 and 83–85.

See Nils Ahnlund, Nils Rabenius (1648-1717). Studier i svensk historiografi, Stockholm 1927.

Regarding the initial observation, it's truly fascinating how our innate pattern recognition systems can connect a simple furrowed stone with such a compeling historical paper trail, showing how even the most subtle tracess can launch a grand quest.